It may be an infant, but that doesn’t mean it’s small. Researchers have discovered a new ‘baby’ planet, at least twice the size of Jupiter, carving a path through a stellar nursery.

Astrophysicists from Monash University have used the ALMA telescope in Chile to discover a ‘baby’ planet inside a protoplanetary disc. But despite being a youngster, this infant is still between two to three times the mass of Jupiter — the most massive planet in our solar system.

The giant ‘baby’ was found inside in the middle of a gap in the gas and dust that forms the planet-forming disc around the young star HD97048. The study — published in Nature Astronomy — is the first to provide an origin of these gaps in protoplanetary discs — also known as ‘stellar nurseries’ because they act as the birthplaces for planets— which have thus far puzzled astronomers.

“The origin of these gaps has been the subject of much debate,” says the study’s lead author, Dr Christophe Pinte, an ARC Future Fellow at the Monash School of Physics and Astronomy. “Now we have the first direct evidence that a baby planet is responsible for carving one of these gaps in the disc of dust and gas swirling around the young star.”

The team discovered the new planet by mapping the flow of gas around HD97048 — a young star not yet on the main sequence, which sits in the constellation Chamaeleon located over 600 light-years from Earth.

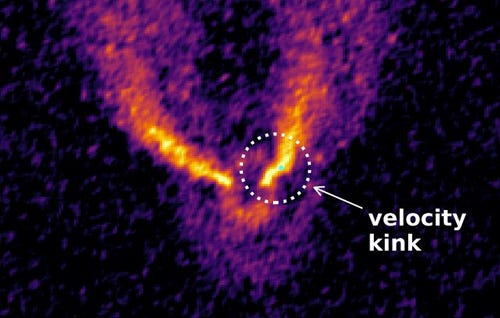

Observing the flow in this material, the team hunted for areas in which the flow was disturbed, in a similar way to disturbance a submerged rock would cause in a stream flowing over it. They were able to ascertain the planet’s size by recreating this ‘bump’ or ‘kink’ in the flow using computer models.

Using the same method of locating ‘bumps’ in gas flow around young stars, the team previously discovered a similar new ‘baby’ planet around another young star roughly a year ago. Those findings were published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

That initial discovery — found in the stellar nursery around HD163296 360 light-years from Earth — was the first of its kind and provided a ‘missing link’ in scientists understanding of planet formation.

These two studies add to what is only a small collection of known ‘baby’ planets.

“There is a lot of debate about whether baby planets are really responsible for causing these gaps,” says Associate Professor Daniel Price, the study’s co-author and Future Fellow at the school. “Our study establishes for the first time a firm link between baby planets and the gaps seen in discs around young stars.”

Original research: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41550-019-0852-6