In the past year, Artificial Intelligence (AI) has really taken off. Algorithms that create stunningly elaborate images or prose are now publicly available. AI is winning art contests and threatning to take over writing. Amidst all this disruption, ethical considerations are becoming increasingly important. However, as one recent paper points out, AI ethics reveals that typically focuses predominantly on a narrow set of principles

“AI ethics discourses typically stick to a certain set of topics con-cerning principles evolving mainly around explainability, fairness, and privacy,” writes AI researcher Thilo Hagendorff, from the University of Stuttgart. “All these principles can be framed in a way that enables their operationalization by technical means. However, this requires stripping down the multidimensionality ofvery complex social constructs to something that is idealized, measurable, and calculable.”

In other words, we’re overlooking important aspects regarding AI ethics, creating big blind spots. With AI already becoming entrenched and the number of applications constantly growing, the window of opportunity to address them may be closing.

The evolution of AI has been rapid, and ethical frameworks have struggled to keep pace. Moreover, the focus on workable ethics — considering just the minimum ethical standard that should be respected before releasing a product — has become the norm. This reflects a broader trend in technology development where fast outcomes are prioritized over complex ethical considerations and long-term impact.

Hagendorff identifies at least three aspects of AI ethics in which we have major blindspots. The first is related to labor.

Human labor in AI

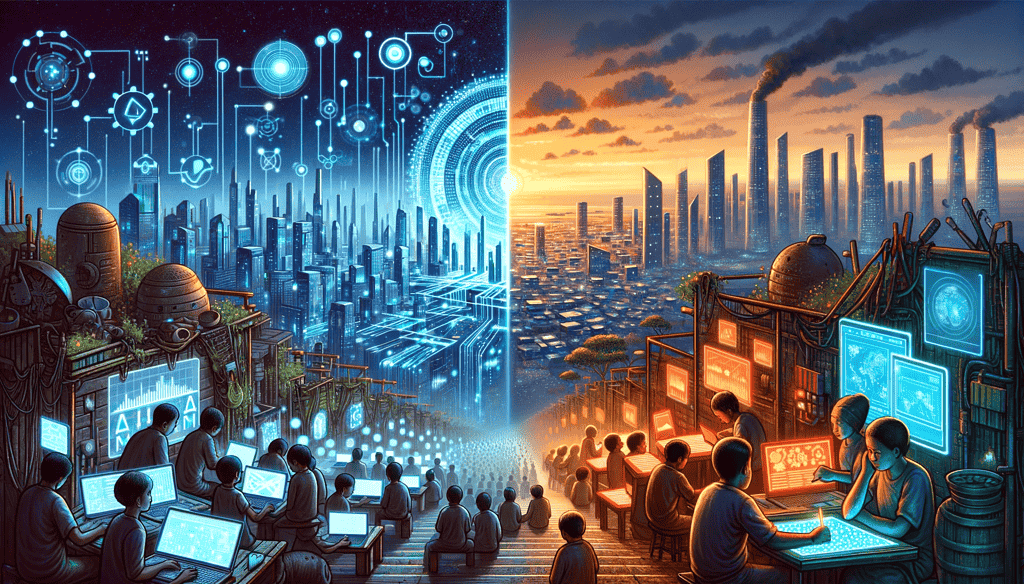

A significant oversight in AI ethics is the reliance on precarious human labor, particularly in data annotation and clickwork. This labor, essential for training AI models, is characterized by low wages and poor working conditions, often in the Global South. AI ethics fails to address these conditions, focusing instead on potential job displacement in developed economies.

“In many cases, AI harnesses human labor and behavior that is digitized by various tracking methods. This way, AI does not create intelligence, but captures it by tracking human cognitive and behavioral abilities,” the researcher explains. This leads to a “data colonialism” and predatory practices of data harvesting.

“An extensive infrastructure for “extracting” valuable personal data or “capturing” human behavior in distributed networks builds the bedrock for the computational capacity called AI. This functions via user-generated content, expressed or implicit relations between people, as well as behavioral traces. Here, data are not the “new oil”, not a resource to be “mined”, but a product of human everyday activities that is capitalized by a few companies.”

AI ethics largely ignores this aspect, focusing instead on potential job displacement in more developed economies. The industry’s dependence on human labor for tasks like transcribing, labeling, and moderating content highlights a significant ethical oversight in the discourse around AI.

Anthropocentrism

The next aspect the researcher focused on is anthropocentrism. Basically, it all focuses on humans.

AI ethics has a strict focus on human-centric issues, largely ignoring the impact of AI on non-human entities, particularly animals. The study points out that AI development often relies on animal testing and has significant implications for animal welfare, aspects rarely discussed in AI ethics.

Some AI research projects also draw upon animals or animal experiments, particularly animal neuroscience, but this is largely ignored. Furthermore, AI research also impacts animals, not only humans.

“AI builds the foundation of modern surveillance technologies, where sensors produce too much data for human observers to sift through. These surveillance technologies are not solely directed towards humans, but also towards animals, especially farmed ani-

mals. The confinement of billions of farmed animals requires technology that can be employed to monitor, restrict and suppress the animal’s agency,” Hagendorff continues in the paper.

AI’s ecological impact

Next up is environmental damage.

The infrastructure supporting AI, from data centers to mining operations for essential components, contributes significantly to environmental degradation. It takes a lot of energy and infrastructure to train AIs. Training GPT-3, which is a single general-purpose AI program that can generate language and has many different uses, took 1.287 gigawatt hours, roughly equivalent to the consumption of 120 US homes for a year. GPT-4 is much larger than GPT-3 — and this is just one engine, and just the training.

The production, transportation, and disposal of electronic components necessary for AI technologies contribute to environmental degradation and resource depletion. This aspect of AI development, masked by the immaterial notion of ‘the cloud’ and ‘artificial intelligence’, demands urgent ethical consideration.

“The term “artificial intelligence” again suggests something immaterial, a mental quality that has seemingly no physical implications. This could not be farther from the truth. To appreciate this, one must switch from a data level, where the real material complexities of AI systems are far out of sight, to an infrastructural level and to the complete supply chain,” the scientist adds.

AI is fast, ethics is slow

AI ethics is a field in the making; in fact, AI itself is a field in the making. But even in its immature stage, AI is causing a lot of disruption and we’d be wise to pay attention to it.

The human labor and environmental costs of AI, often hidden from public view, highlight the need for a more transparent and accountable AI ecosystem.

The current state of AI ethics, with its narrow focus and calculable approaches, fails to address the full spectrum of ethical implications surrounding AI technologies. From the hidden human labor that powers AI systems to the environmental impact and the treatment of non-human life, there is an urgent need to broaden the ethical discourse. This expansion of focus would not only make AI ethics more inclusive and representative of real-world complexities but also bring back the field’s strength in addressing suffering and harm associated with AI technologies.

However, the practicality of enforcing ethical constraints is enormously challenging.

Operationalizing complex social, environmental, and ethical issues into AI systems can be difficult, and there’s a risk that trying to address every ethical concern could hinder innovation and technological progress. The European Union, the political entity most concerned with drafting AI regulation, has repeatedly kicked the can further down the line. Companies can’t really be trusted to self-regulate, and there’s no clear framework for how any regulation of this sort can work.

But awareness is clearly an important first step. We’re all understandably caught in the hype of AI, but there are two sides to this coin, and we also need to pay attention to the pitfalls and hazards in AI. If we, the public, don’t care about this, the chances of companies or governments pushing for more ethical and sustainable AI dwindle considerably.

Ultimately, as AI becomes more embedded in our lives, the ethical considerations surrounding it become more critical to address for the benefit of society as a whole.

The study was published in the journal AI and Ethics.