Recent developments in science such as the detection of gravitation waves by way of the minute displacement of mirrors at LIGO and the development of atomic and magnetic force microscopes to reveal atomic structure and spins of single atoms have pushed the boundaries of what can be defined as measurable.

Yet, as scientists push the limits of mechanical measurements the spectre of Heisenberg’s Uncertainty principle remains to remind that no matter how accurate their equipment and procedures become, nature has an intrinsic, in-built limit to what they can ‘know’.

One of the main results of early investigations in quantum physics, the uncertainty principle says that even as the sensitivity of our measuring equipment improves — these conventional measures are limited by a “measurement backaction”. The most common and easiest to explain example of the uncertainty principle is the idea that knowledge of a particle’s exact location immediately destroys knowledge of its momentum — and by extension, the ability to predict its location in the future.

Sense and sensitivity in laser interferometers

Despite this seeming hinderance, researchers are hard at work developing potential methods to help them ‘sidestep’ Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Thes techniques hinge on the careful collection of only certain information about a system, whilst intentionally omitting other aspects.

So, for example, waves and wavefunctions are of vital importance in quantum mechanics. Using this selective method researchers would attempt to take the measurement of the wave’s amplitude, whilst simultaneously ignoring its phase.

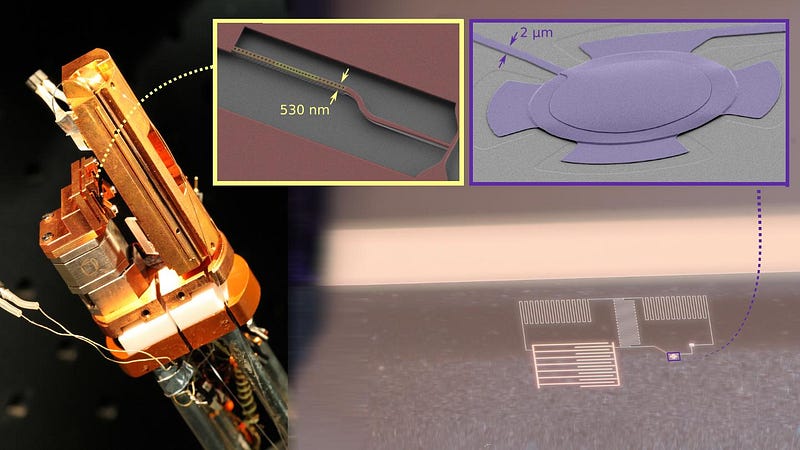

These methods could, in principle at least, have unlimited sensitivity with the drawback of only being able to gauge half of the information about a system. That is the aim of Tobias Kippenberg at Ecole Polytechnique Federale De Lausanne (EPFL). In conjunction with scientists at the University of Cambridge and IBM Research, Zurich, Kippenberg has uncovered new dynamics that place further unexpected constraints on such systems and just what levels of sensitivity are achievable.

The team’s work shows particular interest to the interferometers that are used to measure gravitational waves. The sensitivity of these instruments is of vital importance as gravitational waves are incredibly difficult to detect. As these pieces of equipment use disturbances in laser beams shined down their massive, kilometre-scale arms, improving their sensitivity means trying to avoid backaction in electromagnetic waves.

The team’s study — published in the journal Physical Review X — demonstrates that small deviations optical frequency, coupled with deviations in mechanical frequency can lead to mechanical oscillations being amplified out of control. This mimics the physics displayed in a state physics refer to as “degenerate parametric oscillator”.

This behaviour was found by Kippenberg and his team in two radically different systems — one operating with optical radiation, the other operating with microwave radiation. This is a fairly disastrous discovery as it implies that the dynamics are not unique to any particular system, but rather, are common across many such systems.

The researchers from EPFL investigated these dynamics further — tuning the frequencies and demonstrating a perfect match with pre-existing theories. EPFL scientist Itay Shomroni, the paper’s first author, explains: “Other dynamical instabilities have been known for decades and shown to plague gravitational wave sensors.

“Now, these new results will have to be taken into account in the design of future quantum sensors and in related applications such as backaction-free quantum amplification.”

Original research: Shomroni, A. Youssefi, N. Sauerwein, L.Qiu, P. Seidler, D. Malz, A. Nunnenkamp, T. J. Kippenberg. Two-tone optomechanical instability and its fundamental implications for backaction-evading measurements. Physical Review X 9, 041022; 30 October 2019. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevX.9.041022