The imminent catastrophic threats of climate change, as well as the most recent energy shortages and price hikes due to war and cartels, highlight the need for urgent action toward transitioning away from fossil fuels. But this transition to renewable energy sources could take decades, depending on where you live, and should ideally involve nuclear energy as an intermediate step or even as a permanent hedge in case something goes wrong — for instance, if we get bogged down by intractable battery shortages.

One single golf-ball-sized lump of uranium could supply a lifetime’s energy needs for a typical person, equivalent to 56 tanker trucks of natural gas, and 800 elephant-sized bags of coal — all without the dreadful drawbacks of using fossil fuels. Nuclear energy is responsible for 99.8% fewer deaths than brown coal, 99.7% fewer than coal, 99.6% fewer than oil, and 97.5% fewer than gas. Most of these fossil fuel deaths come from pollution.

The problem is that nuclear energy generally has a largely undeserved bad reputation with the general public, which previously has led to the postponement or outright cancellation of the construction of several proposed new nuclear reactors across the world due to rising pressure from environmental groups.

The risk of a nuclear power plant accident is actually very low and declining, based on data from more than six decades of operation. But if we were to pinpoint the major drawback of nuclear energy, besides the cost, of course, it would be the problem of nuclear waste.

Uranium mill tailings, spent reactor fuel, and other radioactive wastes can remain radioactive and dangerous to human health for thousands of years. Worldwide, experts estimate there are thousands of metric tons of used nuclear fuel that sit in more or less temporary storage containers until we find a better and safer place to deal with it.

“Regardless of whether you are for or against nuclear power, and no matter what you think of nuclear weapons, the radioactive waste is already here, and we have to deal with it,” Gerald Frankel, who is a materials scientist at the Ohio State University, told C&EN. “It’s a societal problem that has been handed down to us from our parents’ generation, and we are—more or less—handing it to our children.”

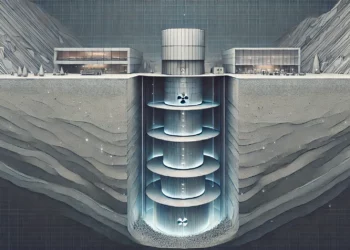

The solution to this growing environmental problem may lie beneath Finland’s frigid forests of Olkiluoto, an island off the country’s west coast. It is here, more than 430 meters (1,400 feet) below ground, that the Finnish government has built the world’s first “nuclear tomb”, meant to safely house nuclear waste for 100,000 years without the fear of leakage.

According to Science, this permanent nuclear waste storage facility was excavated into bedrock that has been geologically inactive for the past billion years. Since it lies between parallel fault zones, the site should be safe from earthquakes at least until the next ice age. Two of the country’s four reactors, which provide nearly 40% of Finland’s electricity, are located on the island, which makes it the perfect location for storing their waste.

The biggest threat, however, is water, which could infiltrate the repository and carry radioactive material to the surface. Olkiluoto’s distinct geology has this covered though, thanks to its gneiss-rich bedrock that makes it very hard for water to seep through.

Although formidable, this geological barrier is not impenetrable, being vulnerable to cracks in the rock — which is why Finland’s nuclear tomb has more than one barrier.

After cooling for a couple of decades in holding pools, spent nuclear fuel rods will be sealed in cast iron canisters. The canisters will then be placed inside another canister made of copper, with inert argon gas forming an extra barrier between the two.

Around 30 to 40 such copper casks will be buried in the tunnel floor, which will be sealed with bentonite, a water-absorbing clay, with yet another barrier made of concrete put on top. By this time, the nuclear waste will finally be left alone for its long vigil that is supposed to last thousands of years, marking the first operational geological disposal facility (GDF) or deep repository.

Even if all of these barriers are breached, it would take decades before escaping radioactive waste migrates to the surface. During all this time, the water’s radioactivity would be dropping. Even under the worst-case scenario, radioactive leakage would be minimal and the exposure would be well below the allowable limit even for people living close to the repository.

“That’s the point of a multibarrier system,” Budhi Sagar, a nuclear expert formerly at the Southwest Research Institute told Science. “Even if some containers fail or a systematic construction error means they all have defects, the geology and other barriers are good enough that you’re still within limits.”

If all goes well during the compliance and licensing process, then Posiva, the nuclear waste company set up by two local nuclear power utilities to develop and manage Onkalo, could begin depositing the first waste in the Finnish bedrock as early as 2024. Given current consumption trends, the repository could be filled to capacity a hundred years from now, at which point the entrance tunnel will be sealed shut.

This proof of concept is extremely important and could have huge implications going forward. No matter where you stand on the nuclear power debate, the reality is that nuclear waste won’t go away. It’s already here and we need a sustainable solution.

The world’s second deep repository could be built near the Swedish coastal town of Forsmark — that’s if the project can pass the many regulatory hoops and have public opinion in favor of it. A similar GDF project planned in the Yucca Mountains in Nevada has been blocked for 20 years, which is why it’s critical that Onkala sets a flawless example for other much-needed repositories to follow.