If you had to pick one practice that changed the human lifestyle, it’s probably farming. Everything changed once people started to farm. The hunter-gatherer lifestyle was over, settlements started becoming more permanent and, of course, what humans ate changed dramatically. Even in coastal areas, people almost completely stopped cooking fish once they started farming crops and animals. But exceptions do exist.

Intrepid farmers who arrived on Northern Europe’s Baltic learned to get the best of both worlds: they stayed true to their farming but developed a mixed diet that embraced both fish and domesticated animal products. Which begs the question: why did they still fish while the others did not?

“How prehistoric farming became established in Northern Europe, a region that supported dense populations of hunter-gatherer-fishers, has concerned archaeologists for over a century,” York University researchers note in their study.

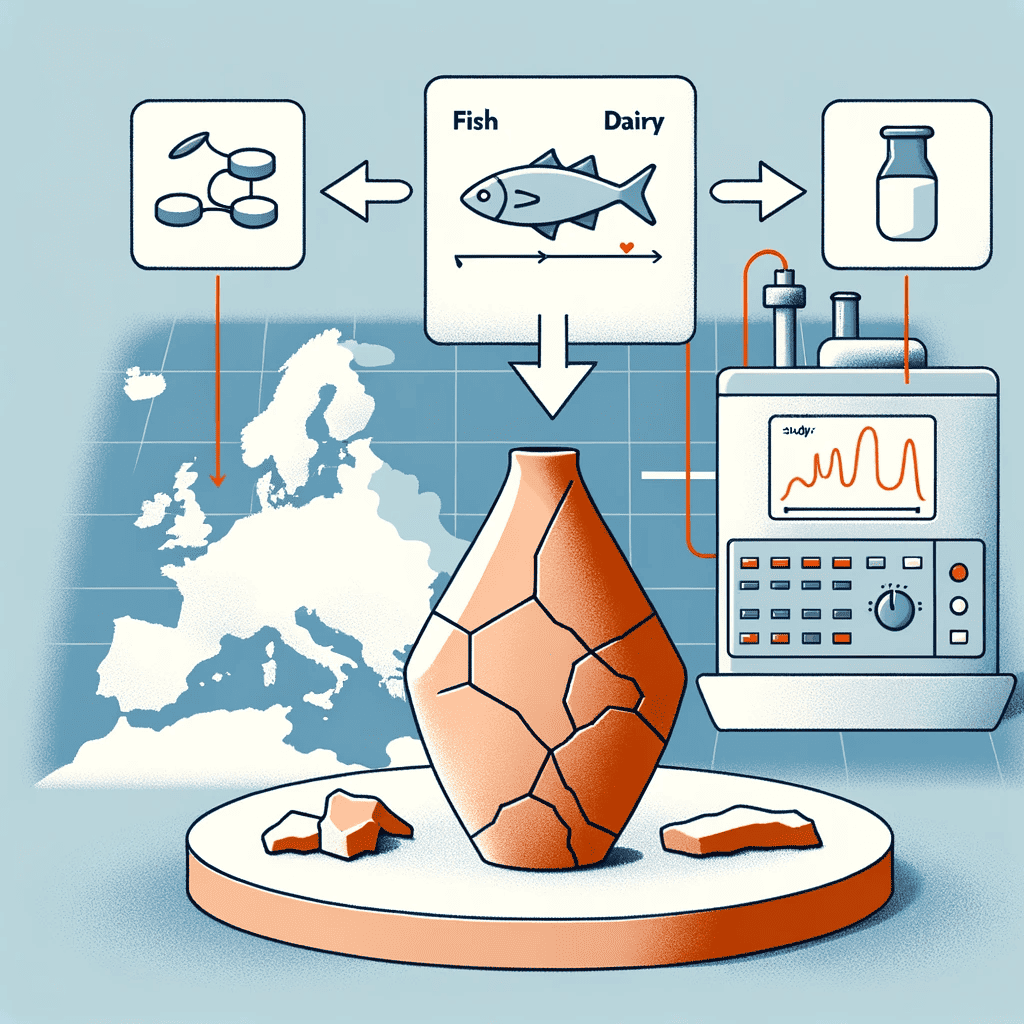

The study aimed to understand how the transition from hunting-gathering-fishing to farming affected culinary practices in Northern Europe (from Denmark to Finland). The study focused on the analysis of organic residue found in over 1,000 pottery vessels from both hunter-gatherer-fisher and early agricultural sites.

Despite the transition to farming, there was a surprising continuity in the use of aquatic foods and wild plants. Both hunter-gatherer-fishers and farmers used pottery in similar ways, suggesting a hybrid lifestyle where people farmed, but also foraged, fished, and hunted.

The analysis, which involved a process called gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, shows the different types of organic substances the fats and lipids originated from. Remarkably, 50% of the farmers’ pottery contained fish-based residues, and 5% of them contained traces of dairy.

Unfortunately, we still don’t know why people in this particular area continued to have a mixed diet, unlike other populations at the time. Professor Oliver Craig, Director of the BioArCh Lab at the University of York, where the study was conducted, said:

“Our findings suggest that early farmers moved to this region rich in aquatic resources and adapted their economy and daily habits, such as diet and cooking practices, by observing indigenous hunter-gatherer-fishers they encountered. While this might seem like an obvious and logical strategy, it is in significant contrast to virtually all other Early Neolithic sites that are located in coastal areas, where we see no evidence that they made use of marine resources.”

“We may never know for sure why these early agriculturalists embraced a fish diet while farmers in other regions comprehensively rejected aquatic resources. So far, genetic studies suggest there was very little intermarriage between farmers and hunter-gatherers, however, the archaeological record suggests that the hunter-gatherer-fisher population was particularly well-established in this area when the first farmers arrived from Central Europe and the Eurasian Steppe. Perhaps these communities exerted a strong influence on new arrivals resulting in an element of cultural blending between the two groups.”

Co-author of the study, Harry Robson from the Department of Archaeology at the University of York said this shows that the transition from foraging to farming was not that homogeneous, but was rather a complex and nuanced process.

“It is intriguing that, aside from the Danube Gorges, this is the only region in Europe where this practice takes place. Equally, whilst it has long been recognized that the hunter-gatherer-fishers of the Ertebølle culture interacted with farmers across a frontier zone, we have the first widespread evidence that commodities, including dairy products, were exchanged,” Robson says.

There are many unanswered questions regarding this transition, says Dr Alexandre Lucquin, also an author of the study. But one thing’s for sure: once this transition happened, humanity would never be the same again. Maybe studies like this one can, in time, help us understand what happened.

“There are many unanswered questions surrounding why people in Europe made such a large-scale and definitive shift to farming at this time. Perhaps they believed this new lifestyle offered more predictable resources,” Lucquin concludes.

“Once the Neolithic revolution began there was no going back for humanity and we may never really know what happened to the last hunter-gatherers of Europe.”

The study was published in PNAS.