Instead of a linear progression with a beginning and end, the story of the human evolution is a complex and winding tale. It’s a tale of a family tree whose branches stretch over many millennia and continents, often in unexpected ways. Scientists are still revealing what our ancient relatives were like and how they adapted to life in different landscapes. Sometimes, these adaptations were outright strange.

They made baseball-sized spheres — and we’re not sure why

These limestone spheroids are one of the least understood items from our ancient relatives. They appear to have been created on purpose millions of years ago — but we don’t really know why. Earlier this year, researchers examined 150 spheroids dating back from 1.4 million years ago from a site north of modern-day Israel.

These intriguing objects have baffled researchers, with some even proposing they might have been accidental byproducts of other activities. In a recent study, researchers used 3D analysis methods with the collection of spheroids and found they were crafted with a premeditated reduction strategy — so they were made on purpose, not by accident.

However, they couldn’t determine why the spheres were crafted. Previous studies suggested hominins were likely trying to make tools but this is still up for debate.

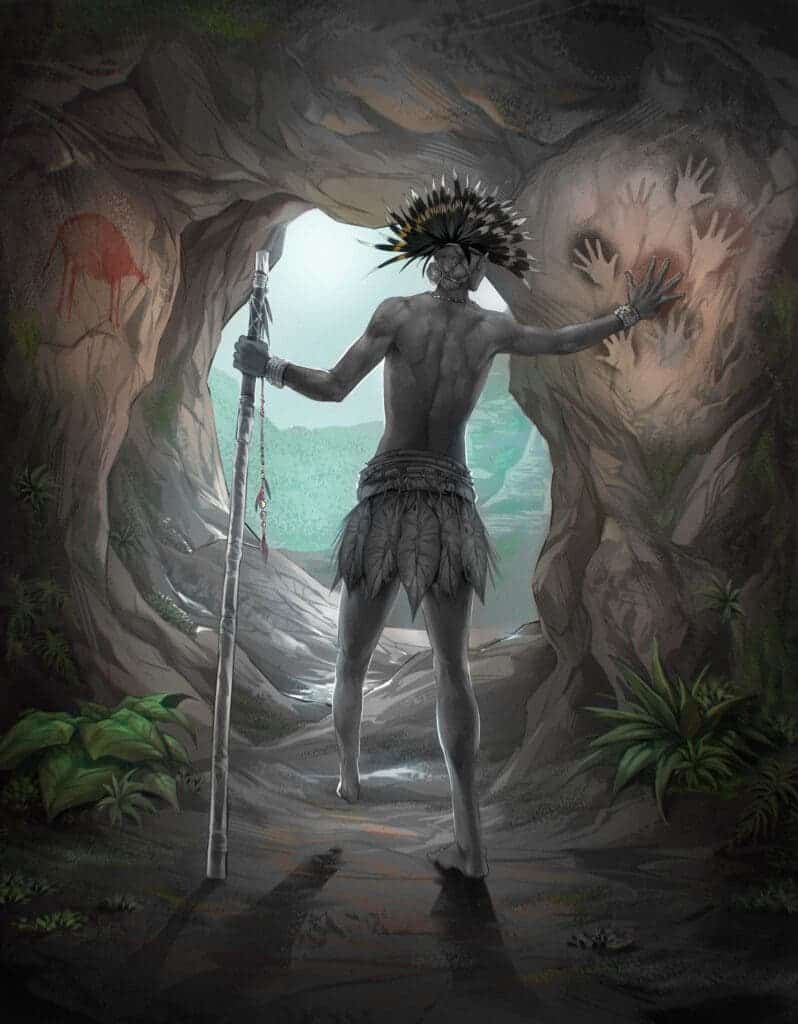

They colonized rainforests with tool miniaturization

Miniaturization isn’t just a recent trend; it’s an ancient practice dating back 45,000 years, according to a new study. Hunter-gatherers in the Sri Lankan rainforests mastered this technique for more effective hunting and foraging.

Hunter-gatherers in the Sri Lankan rainforests used miniature stone tools and bone projectiles to ensure successful hunts, a study earlier this year showed. The researchers recovered artifacts from the Kitulgala Belilena, a cave that’s one of Sri Lanka’s most famous archeological sites, with a wealth of stone tools.

They established that humans consistently inhabited this rainforest area between 45,000 and 8,000 years ago and manufactured miniaturized stone tools. They would get pebbles or stones from streams for processing and then place them on a rock anvil, striking them with a hammerstone. The small flakes would then be used for projectiles.

This behavior demonstrates their deep understanding of sustainability and ecological balance.

They interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans

A century-old collection of ancient teeth found earlier this year suggests the presence of a mixed population of Neanderthals and modern humans on the islands between France and Britain. This discovery further supports the existing evidence indicating multiple instances of interbreeding between these two groups throughout history.

This interbreeding wasn’t a rare event but rather a series of interactions that occurred over thousands of years and across different regions. As a result, most people today who have non-African heritage carry a small percentage of Neanderthal DNA. In some populations, particularly in Oceania and parts of Asia, there is also a notable presence of Denisovan DNA. This genetic legacy is not just a historical footnote; it has practical implications for us today. For instance, some of the Neanderthal and Denisovan genes we carry are thought to influence aspects of our immune system, while others may affect our skin and hair.

Neanderthals are believed to have disappeared about 40,000 years ago, coinciding with the emergence of modern humans from Africa. However, there was a significant period of overlap between the two. The prevailing consensus among researchers is that Neanderthals and modern humans coexisted for a minimum of 5,000 years and interbred more than one time in their history.

They performed surgeries

Archaeologists discovered earlier this year a 31,000-year-old burial of a young adult with a missing lower left leg. The limb wasn’t chewed off by animals or severed by other humans during a conflict. Instead, it seems to be the mark of surgery, an intentional medical act, which suggests surgeries are much older than we thought.

The researchers believe the scalpel was made from the sharp edge of a rock, bamboo or marine shells. Following the operation, the individual was likely fed, bathed and had its wounds cleaned as part of the recovery. It all indicates the surgery was successful as the young adult didn’t suffer from infection and lived six to nine years after the surgery.

They made beds 200,000 years ago

At the historically rich Border Cave, nestled between South Africa and Swaziland, archaeologists unearthed a glimpse into our ancient ancestors’ lives. Something we’re all fond of. Of course, I’m talking about a bed. The discovery of three ancient beds made from grass, strategically placed on layers of ash at the back of the cave, reveals early humans’ innovative approach to comfortable living and pest control.

This ash, a natural insect repellent, highlights their understanding of their environment. Further intriguing finds include signs of fire-making, and the use of tarchonanthus (camphor bush) known for its insect-repelling properties, pointing to a sophisticated grasp of health and hygiene practices.

The grass for the beds wasn’t directly visible and the researchers had to use magnification and chemical analysis to identify it. While they acknowledge they can’t know for sure whether people slept on the grass, the fact that there was plenty of grass material intentionally brought into the cave suggests that this is very possible.

Plenty to discover

By working with fossil traces, scientists are frequently revealing new information about our ancient relatives. There’s still a lot we don’t know but as research moves forward, we’ll have a better idea of their lives thousands of years back. For now, these five surprising things we learned this year help us unpack the story of human evolution.