The holiday season of December comes with peaceful Christmas celebrations and some pretty rowdy New Year fireworks and parties. But while us humans can get accustomed to that, for wild animals, fireworks can be terrifying.

For animals, and birds in particular, fireworks aren’t just a nuisance — they’re a harrowing experience. A new study, led by Bart Hoekstra from the University of Amsterdam used weather radar data and systematic bird counts to analyze just how much distress fireworks bring. The researchers found that on New Years Eve, there are approximately 1000 times as many birds in flight than on other nights.

Big firewords, big problems

The scale of the disturbance is striking.

“We found that fireworks-related disturbance decreased with distance, most strongly in the first five kilometers, but overall flight activity remained elevated tenfold at distances up to about 10 km,” the researchers write.

“New Years Eve fireworks alone may not be lethal, but the disturbance they cause extends well into protected waterbodies and occurs during winter.”

In addition to the initial shock, fireworks also have other consequences. The immediate consequence is an increased energy expenditure for birds, which can have lasting effects on their foraging behavior and energy reserves. The fireworks could also push birds to change their habits or preferred sites, which could have long-term detrimental effects on some bird communities.

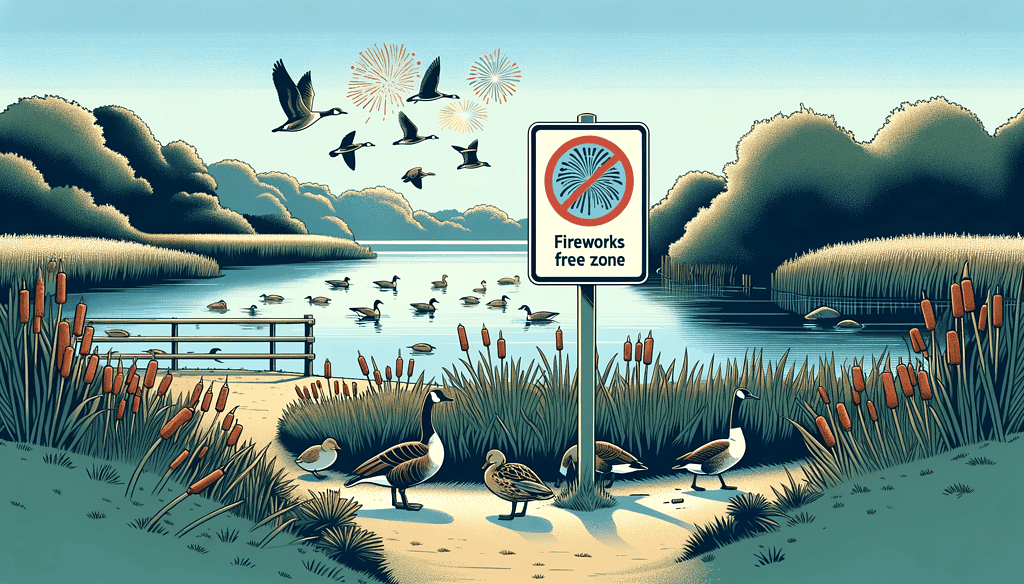

The research also highlights that the response to fireworks is not uniform across all bird communities. Larger-bodied birds in open habitats, such as geese and ducks, exhibited a stronger flight response than smaller-bodied species in more sheltered environments like forests. This difference in response is crucial for conservation strategies, suggesting that mitigation efforts should focus on protecting large-bodied bird species in open habitats.

Solutions that can actually work

The study focused on the Netherlands, but there’s no real reason to suspect things are much better in other parts of the world. Which begs the question, how could we then protect these animals?

Of course, the best thing for wildlife would be to simply not use any fireworks, but that’s probably not realistic for the time being. But the study also explores some solutions that are more applicable.

For instance, the researchers propose establishing fireworks-free buffer zones around sensitive habitats. Another approach is limiting fireworks displays to urban centers where there are fewer birds and the fireworks’ impact is lessened. Another option would be to transition towards soundless fireworks. Drone shows have emerged as a lower-impact alternative to traditional fireworks, but the impact of these drone shows is not fully understood.

However, given the scale of disturbance observed, the researchers suggest that the only true solution would be to simply use less fireworks.

“Ultimately, however, a drastic reduction in the use of fireworks may be the only feasible option for substantially mitigating the impacts of this disturbance on birds,” the researchers conclude.

The study was published in the journal Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.