It’s nearly impossible to mention asbestos in a conversation and not have someone reply “doesn’t that give you cancer?” — and, to be honest, yes it can. In fact, that’s just one of the conditions that exposure to asbestos can cause.

But how, and why does this happen? What even is asbestos, to begin with? Let’s find out.

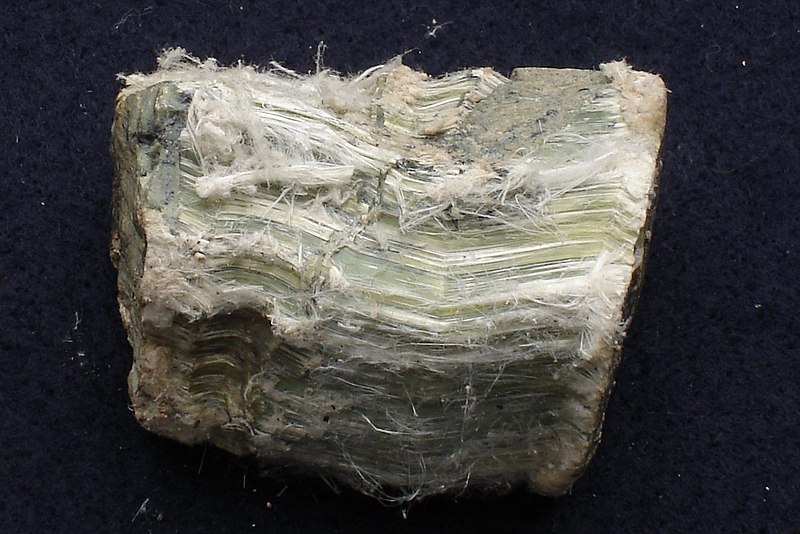

A pretty mineral

Asbestos is a silicate rock, which is hands-down the most abundant family of minerals on Earth. This means that it’s chemically related to stuff like sand or clay. Technically speaking, “asbestos” is a commercial and legal term, not a geological one. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, it broadly denotes six naturally occurring silicate minerals. All six share the same apparent structure and physical properties (most notably high electric and thermal resistance). Asbestos crystallizes in bunches of long, thin, fibrous crystals; these are, in turn, bunches of shorter, thinner ‘fibrils’.

The Asbestos Hazard Emergency Response Act (AHERA) defines six minerals as being asbestos:

- chrysotile (white) asbestos;

- grunerite asbestos, also known as amosite or brown asbestos. This has the distinction of belonging to the epically-named cummingtonite solid series of minerals;

- riebeckite asbestos, also known as crocidolite or blue asbestos;

- anthophyllite;

- tremolite;

- actinolite;

The last three saw limited to no commercial use and are generally considered to be impurities in other minerals.

The most recognizable form of asbestos (and the most abundant in nature) is chrysotile asbestos. Frankly, I find it to be quite beautiful. A sample of this mineral, as weird as this sounds, kind of looks like a stone that’s shedding its fur. That ‘fur’ being made up of fibrous crystals and fibrils. The chemical links between individual asbestos crystals are very weak, so even light touches can make them flake off the sample. Tremolite asbestos is also very pretty (and the type shown on the Wikipedia page for asbestos).

Image credits Eurico Zimbres.

A useful mineral

Because of its physical properties, asbestos has seen extensive use as an insulating and building material. It was also used in ancient ceramics up until, roughly, the year 200 AD. Egyptian pharaohs embalmed from 2000-3000 B.C. were wrapped in asbestos cloth to better preserve their bodies. Khosrow II of the Sasanid dynasty — who expanded ancient Persia to its largest size in the early 7th century — is said to have had an “asbestos napkin” which he would clean by “simply throwing it into [the] fire” to amaze his guests.

That last tidbit is great to showcase why asbestos saw extensive use in the early-mid industrial era: it’s fire-proof under most conditions. Together with its availability, low conductivity to heat and electricity, and quite high mechanical resistance, it makes asbestos a very useful substance. Unlike wool or modern insulating foams, it’s fire-retardant; unlike most fire-retardants today, it’s also a good and versatile insulator.

The tail end of the 19th century saw an explosion in the use of asbestos. Considered somewhat of a wonder material at the time, it was used for fire-retardant coatings, mixed in concrete, bricks, pipes and fireplace cement, for heat-, fire-, and acid-resistant gaskets, pipe insulation, ceiling insulation, fireproof drywall, flooring, roofing, lawn furniture, and drywall joint compound.

People also spun asbestos rope and yarn, lined clothes irons with it, and integrated it into a variety of other consumer goods. Most buildings constructed before the late 1990s contain asbestos in some shape or another. Back in 2011, over 50% of UK houses still contained asbestos, according to The Guardian.

It was even spun into cloth which was so widely used that there are entire legal groups today which specialize in asbestos-related litigation.

Which neatly brings us to it being:

A very toxic mineral

Image credits Harald Weber.

The properties that make asbestos fibers flake off so easily are the same that make it so ridiculously bad for you.

Asbestos, even when spun into cloth or mixed in with other materials, will break down into teeny tiny bits or dust. Cutting a piece of asbestos wool to size will release such fragments. Using an asbestos glove will release such fragments. Do you mine or work with raw asbestos in any way, shape, or form? You’re inhaling tiny fragments of it. Did you build and/or serve on U.S. navy ships roughly before the 1980s? You probably have cancer now. Do you live, work, or hang out in buildings that include asbestos? Tiny fragments yet again. Do you like to punch old drywall for fun? Wear a mask.

Its toxicity increases over time as asbestos crystals break down due to wear and tear, creating tiny bits that float off; age also increasing the quantity of dust generated when it is handled. Asbestos products such as cement will release fragments when manipulated or broken even decades after they were produced.

Now, the fact that it breaks down isn’t, in itself, that much of an issue. Nobody likes to breathe in dusty air but it won’t slowly kill you. The problem with asbestos is that, chemically, it’s very similar to glass. When it breaks down, it forms tiny, sharp, and hard fragments. For the soft tissues of your lungs, inhaling asbestos dust is like breathing in razor blades. Exposure to asbestos can thus lead to pulmonary fibrosis and asbestosis, conditions that involve severe breathing issues due to repeated and sustained damage and subsequent scarring and thickening of lung tissues. Over time, this damage can lead to lung cancer, mesothelioma, and pulmonary heart disease.

The first reports that asbestos exposure is a major health hazard arose in the early 1900s in the UK, France, and Italy. The first diagnosed death due to asbestosis was recorded in 1924, and an official report was presented to the UK Parliament on 24 March 1930, leading to safety regulations that went into effect in 1932.

Today, exposure to asbestos fibers is considered universally dangerous. Any work that involves exposure to friable asbestos materials, or which involves materials and processes that can cause the release of loose asbestos fibers, is considered high-risk.

Asbestos fibers do not evaporate or dissolve in air or water. In general, they can get cleared out or degraded in your lungs, but they’re likely to get trapped there and keep causing damage. The slow, steady buildup of such fibers in the lungs, as well as their potential to keep causing harm long after exposure, slowly leads to health issues. For example, the first confirmed victim of asbestos-caused pulmonary fibrosis worked for 14 years in an asbestos textile factory.

Only two countries today do not have a ban on asbestos in place — Vietnam and the United States. Other countries employ a mixture of outright bans on the use of asbestos or certain types of asbestos, or heavy regulation for asbestos or the products that contain it.

If you do have reason to believe you’ve been exposed to asbestos or asbestos dust, it’s best that you speak to a doctor as soon as possible.