New research looking at some old fossils uncovers a novel species of amphibians. The animal belonged to the albanerpetontid family and provides the oldest known evidence of a slingshot-style tongue.

The fossils had been previously analyzed and mistakenly interpreted as belonging to a species of ancient chameleons. However, the new study comes to show that despite having lizardlike claws, scales, and tails, albanerpetontids (or ‘albies’) were actually amphibians. They belonged to a lineage that’s distinct from modern frogs, salamanders, and caecilians. This lineage developed over some 165 million years and died out roughly 2 million years ago.

The fossils described in this study are roughly 99 million years old, and help showcase how the albies hunted: lying in wait for potential prey, then launching their tongue at them, similarly to modern chameleons. This fossil specimen (previously misidentified as an early chameleon) is the first albie discovered in modern-day Myanmar and the only known example in amber. The species was christened Yaksha perettii, after treasure-guarding spirits known as yakshas in Hindu literature and Adolf Peretti, who discovered the fossil.

Don’t judge a fossil by its tongue

“This discovery adds a super-cool piece to the puzzle of this obscure group of weird little animals,” said study co-author Edward Stanley, director of the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Digital Discovery and Dissemination Laboratory. “Knowing they had this ballistic tongue gives us a whole new understanding of this entire lineage.”

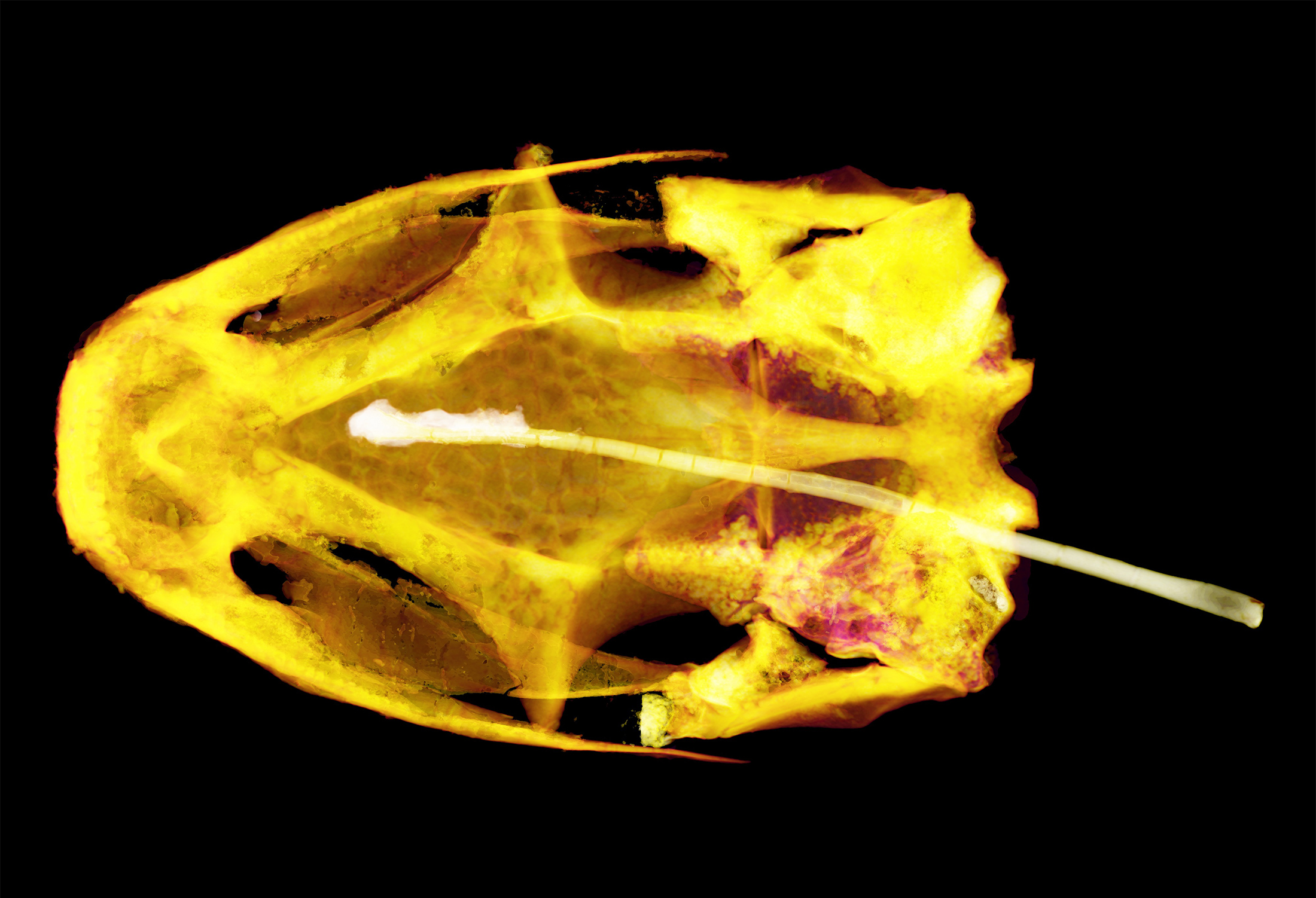

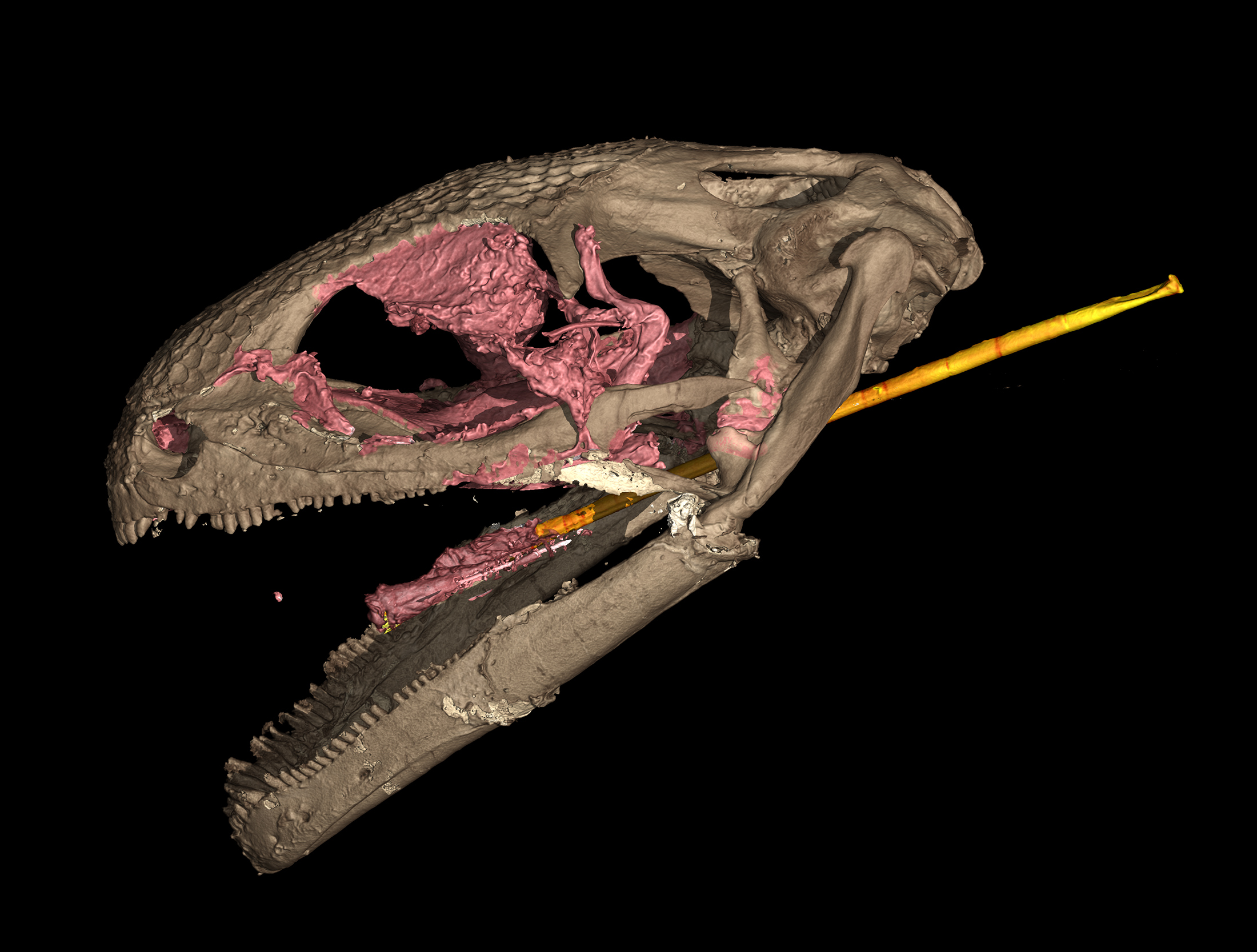

The initial misidentification of the species came down to the fossils it was described from: a juvenile individual with a hodgepodge of characteristics, including a specialized tongue bone. The paper describing them sparked an international collaboration to better correctly identify the fossils, after Susan Evans, professor of vertebrate morphology and paleontology at University College London and an albie expert, recognized some of the characteristics. Together with Peretti, the researchers sent the specimen together with similar amber-encased ones to the University of Texas at Austin for computer tomography (CT) scanning.

It was found that the amber-encased specimen was in “mint condition” (which tends to be rare for albies). It was also, luckily, an adult counterpart of the juvenile that has previously misidentified.

“Everything was where it was supposed to be. There was even some soft tissue,” says Evans.

The excellent quality of the specimen allowed the team to dispel some wrong assumptions about the species. Their reinforced skulls have led researchers to hypothesize that they were a species of digging salamanders. Several other shared features, most notably their claws, scales, and large eye sockets, were also reminiscent of reptiles. The albie also likely had a ballistic tongue similar to those of chameleons today.

Based on the skull, the researchers estimate that Y. perettii was about 2 inches long, not including the tail. The juvenile was a quarter that size. It relied on its fast tongue (the chameleon tongue can go from 0 to 60 mph in a hundredth of a second, being one of the fastest muscles in the animal kingdom) to hunt for insects, and would otherwise try to keep hidden among the brush, the team believes.

Its predatory nature and projectile tongue also help explain its other “weird and wonderful” features, including unusual jaw and neck joints and large, forward-looking eye sockets. It’s also likely they breathed through their skin like salamanders do, but this is still unconfirmed.

Although the specimens were in excellent condition, the team remains unsure where they fit in the amphibian family tree due to its unusual combination of features.

“In theory, albies could give us a clue as to what the ancestors of modern amphibians looked like,” Evan says. “Unfortunately, they’re so specialized and so weird in their own way that they’re not helping us all that much.”

No albies are known to have survived to modern times, but they only faded out about 2 million years ago — which means they might have crossed paths with our earlier hominid relatives.

“We only just missed them. I keep hoping they’re still alive somewhere,” Evan adds.

The paper “Enigmatic amphibians in mid-Cretaceous amber were chameleon-like ballistic feeders” has been published in the journal Science.