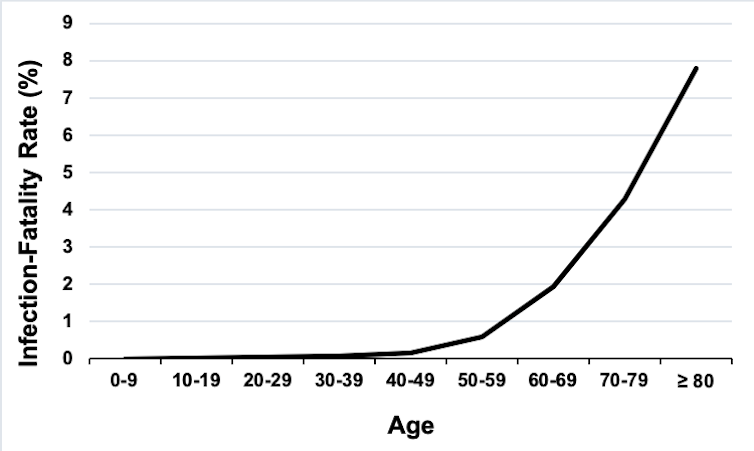

The fatality rate for the disease is estimated to be 0.66%, according to data from China. In other words, 0.66% of people who are formally diagnosed with COVID-19, die. But the rate varies dramatically for different age groups, ranging from 0.0016% for children under ten to 7.8% in people over 79. Similar rates are seen in New York city.

The graph below shows the increasing fatality rate for increasingly older populations.

Similar trends are seen with the percentage of COVID-19 patients that need hospitalisation (ranging from 0% in under tens to 18.4% in over 79s). Yet those over 79 do not appear to be more likely to become infected, as they represent just 3.15% of the total confirmed cases.

Recent studies have shown that gender is a risk factor, too. Men are at a greater risk of dying from COVID-19 than women.

Data from China shows that men have 1.65 times the risk of dying from COVID-19 and in New York city, the rate is 1.77 times greater. Yet overall, men and women have roughly similar risks of getting the virus.

A declining immune system?

The ability of the human immune system to fight off pathogens declines over time and is significantly reduced in those over 70. Recent results show that in bad cases of COVID-19, there is a severe deficiency in certain classes of immune cells that fight off infections. These immune cells are known to be less active in the elderly, suggesting that an age-related decline in immune function may put the elderly at risk of more severe COVID-19 disease. Yet many of the most severe cases of COVID-19 are associated with over activation of the immune system.

The immune system is composed of many different parts and so it is possible to have suppression of one component and over-activation of another. But if the age-dependency of COVID-19 disease was specifically due to immune function, we would expect babies to also show severe disease, as their immune systems are still developing. This is what is seen in most seasonal flu epidemics, where those under two and those over 65 are at a greater risk of severe disease.

Changes in ACE2 levels?

In contrast to the flu, the 2003 Sars epidemic showed a fatality rate that increased with age similar to COVID-19 (4.26% for those under 44, rising to 64.2% for those over 74) and a 1.66 times greater fatality rate in men compared with women. The absence of severe infection in babies suggests that the age and gender disparity for COVID-19 may not be due to differences in immune response but rather something specific to the Sars viruses.

Both the 2003 SARS-CoV-1 and the current SARS-CoV-2 viruses bind to and use a protein known as ACE2 to gain entry into cells. ACE2 normally helps to regulate blood pressure and is found on the surface of many different cells, including those that line the lungs. The amount of ACE2 on human cells is higher in men and increases with age.

Certain variants of the ACE2 gene in humans are also associated with different levels of ACE2 expression, and the amount of ACE2 in different populations is somewhat correlated with COVID-19 disease. Also, hypertension (high blood pressure) is known to be a significant age-dependent risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease. Hypertension is typically treated with ACE-inhibitors that have also been shown to increase the amount of ACE2.

However, it appears that COVID-19 infection results in decreased ACE2 levels, which are associated with more severe lung disease. It is not clear what happens when ACE2 levels are high to begin with, such as in older men. Simply increasing ACE2 levels does not appear to cause more severe disease.

In addition, a recent clinical trial showed that ACE-inhibitor use was associated with less severe COVID-19 disease.

ACE2 is just one component of a complex regulatory system and so changes in ACE2 levels and action may have more complicated effects on disease progression than just virus entry into cells. These effects may change as the disease progresses and the immune system is activated.

Exposure to other coronaviruses?

Other related coronaviruses have been found to cause pneumonia in elderly patients and the likelihood of exposure to a virus increases with age. We also know that the human immune system can show some cross-reactivity between different coronaviruses.

Normally, recovery from an infection generates an immune memory that protects a person from being reinfected with the same pathogen. Cross-reactivity occurs when the immune system responds to a new pathogen as if it already had a memory of it. Sometimes this can protect against infection, but sometimes it can make the disease worse.

As severe COVID-19 disease appears to result from an over-activation of the immune system, it is possible that previous exposure to related coronaviruses may create an immune memory that primes the system to overreact to COVID-19. This process could be more prevalent in older people with more past exposure to other coronaviruses.

No data shows this cross-reactivity occurs in COVID-19 disease, but analysis of COVID-19 severe infection rates in areas with previous related coronavirus outbreaks could shed some light on the matter.

A simple explanation?

It is also possible that the reason why more men and elderly people are dying from COVID-19 is more simple. We know that the risk of fatal COVID-19 disease is almost twice as great if the person has underlying health conditions. Most of these health conditions show increasing prevalence with age, such as hypertension, which increases in occurrence from 7.5% in those under 40 to over 63% in those over 60. This increasing rate of predisposing health conditions could directly increase the risk of severe COVID-19 disease.

We don’t know why these health conditions put people at risk of more severe disease. We also are just beginning to understand how COVID-19 causes disease in the first place. By understanding the process of severe COVID-19 disease we will be better placed to both mitigate the risks to specific populations and to develop interventions that block the most severe disease and possibly even prevent fatalities.![]()

Jeremy Rossman, Honorary Senior Lecturer in Virology and President of Research-Aid Networks, University of Kent

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.