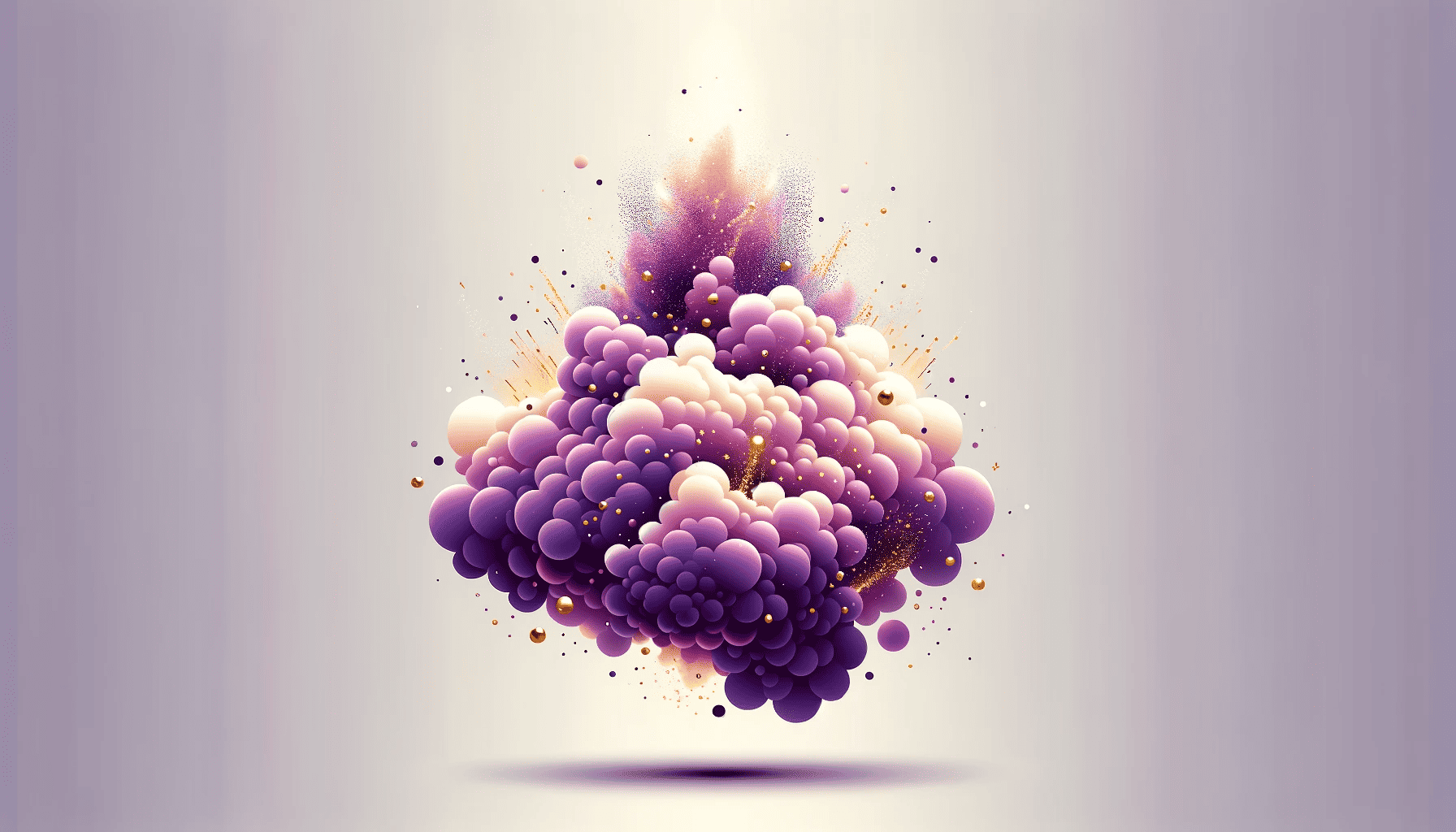

Researchers at the University of Bristol have cleared up a 400-year-old mystery: why fulminating gold, an explosive from the 16th century first discovered by alchemists, emits purple smoke upon detonation.

Fulminating gold is a complex mix, primarily powered by ammonia. First documented by Sebald Schwaertzer in 1585, its purple smoke baffled many, including chemistry legends like Robert Hooke and Antoine Lavoisier. Despite centuries of chemical advancements, this colorful enigma persisted — until now.

Surprise, surprise — apparently, it all boils down to gold nanoparticles released during the violent discharge. But there’s more to this story than meets the eye.

Alchemy to Chemistry

During the late Middle Ages, alchemy was extremely fashionable. Part speculative philosophy, part precursor to legitimate chemistry, alchemy aimed to achieve the transmutation of base metals such as iron into gold. Alchemical side quests included a universal cure for all diseases and the discovery of a means to achieve eternal life.

Although it is easy to ridicule alchemists with our fancy scientific knowledge of today, let’s not forget people of the time were working with very limited tools and knowledge. For instance, Medieval scholars still held to the assumption that everything in the universe is composed of four elements: fire, air, earth, and water.

Nevertheless, it was alchemists who first produced hydrochloric acid, nitric acid, potash, and sodium carbonate. They were also the first to identify chemical elements such as arsenic, antimony, and bismuth. Though shrouded in the occult and pseudoscience, it was alchemy that laid the groundwork for chemistry as a scientific discipline.

It was in these shadowy labs of medieval alchemists that the intriguing properties of fulminating gold were first revealed.

Gold: the explosive

Fulminating gold, or gold(III) fulminate, differs significantly from the lustrous metal known to us. It’s a powdery substance, prone to exploding upon the slightest disturbance. Its volatility is owed to its molecular structure, where gold atoms are linked to highly unstable nitro groups. Even minor disturbances can break these bonds, releasing energy violently.

Synthesizing fulminating gold involves a delicate process of reacting gold with nitric acid and ethanol. The procedure is fraught with risks, as the compound can detonate unexpectedly. It’s no surprise that fulminating gold was the first high explosive in the world, used extensively in mining and warfare.

Besides being incredibly explosive and the fact that it’s made with gold particles, one of the more curious features of fulminating gold is that it detonates in purple smoke. Although chemists have had their theories, no one really had been able to clearly prove why this occurs — until recently.

Professor Simon Hall and his Ph.D. student Jan Maurycy Uszko at the University of Bristol detonated tiny 5 mg samples of fulminating gold on aluminum foil and captured the resulting smoke with copper mesh. Under the scrutiny of a transmission electron microscope, a long-held yet unproven suspicion was confirmed: the smoke contained spherical gold nanoparticles.

“We found the smoke contained spherical gold nanoparticles, confirming the theory that the gold was playing a role in the mysterious smoke,” said Professor Hall.

“I was delighted that our team have been able to help answer this question and further our understanding of this material,” he added.

The spherical gold nanoparticles ranged in size from 30 nanometers to 300 nanometers, which is relatively close to 400 nanometers — the wavelength of violet light. This analysis not only demystifies the purple smoke of fulminating gold but also explains why objects in alchemy labs were often coated in a purple patina.

The findings appeared in pre-print on arXiv.

The quest for understanding continues, bridging centuries of human curiosity and intellect.