When the nature of lichens was discovered 140 years ago, they became the most prominent example of symbiosis, a term that defines a mutually beneficial relationship between two dissimilar organisms.

In the case of lichen, the filaments of a single fungus create protection for photosynthetic algae or cyanobacteria, which provide food for the fungus in return. However, a new study reveals that there is actually a third organism involved in this relationship – a yeast that likely provides the structure for “leafy” or “branching lichens.”

“These yeast are sort of hidden just below the surface,” said John McCutcheon, a genome biologist at the University of Montana, and senior author of the study. “People had probably seen these cells before and thought they were seeing something else. But the molecular techniques we used happened to be especially good for spotting the signal of a separate organism, and after years of looking at the data it finally occurred to us what we were seeing.”

McCutcheon’s team made the discovery after studying two lichen species obtained from Missoula, Montana mountains – Bryoria fremontii and B. tortuosa. Despite B. tortuosa possessing a yellow color due to the presence of vulpinic acid, genetic tests revealed identical fungus and alga in both species. However, they also discovered the genetic signature of a third species – a basidiomycete yeast – in both species, although it was more abundant in B. tortuosa.

Additional testing of 56 different lichens from around the world revealed that each one has its own variety of basidiomycete yeast, suggesting that lichens actually comprise a threesome, not a couple, essentially rewriting 150 years of biology.

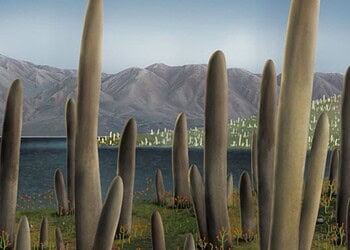

The team believes that this newly discovered yeast could play a role in creating the large structures seen in macrolichens, which would explain why these particular lichens are hard to grow in the lab when using just a fungus and alga.

“This doesn’t prove that they’re necessary to create the structure of the macrolichens, or that they do anything else for that matter,” McCutcheon said. “But its early days. It took a lot of work just to discover that they were there. We’re interested if the yeast is making these important compounds, or possibly enabling the other fungus to make them. We don’t know, but it’s the obvious next question.”

Journal Reference: Basidiomycete yeasts in the cortex of ascomycete macrolichens. 21 July 2016. 10.1126/science.aaf8287