When we look at the sky, we see different types of objects. Some are man-made (like the International Space Station), some are from our solar system (like Venus or Saturn), but many are twinkling, shiny objects — of course, stars from outside our solar system.

Stars have fascinated humans since time immemorial, especially because sometimes, they seem to twinkle. Stars don’t actually twinkle per se — the twinkling we observe here has more to do with the atmosphere on Earth rather than the stars themselves. There are three main factors that influence how stars “twinkle”, and to truly understand them, we need to take a short dive into some atmospheric physics.

Turbulence

The first physical phenomenon that makes stars appear to twinkle is turbulence.

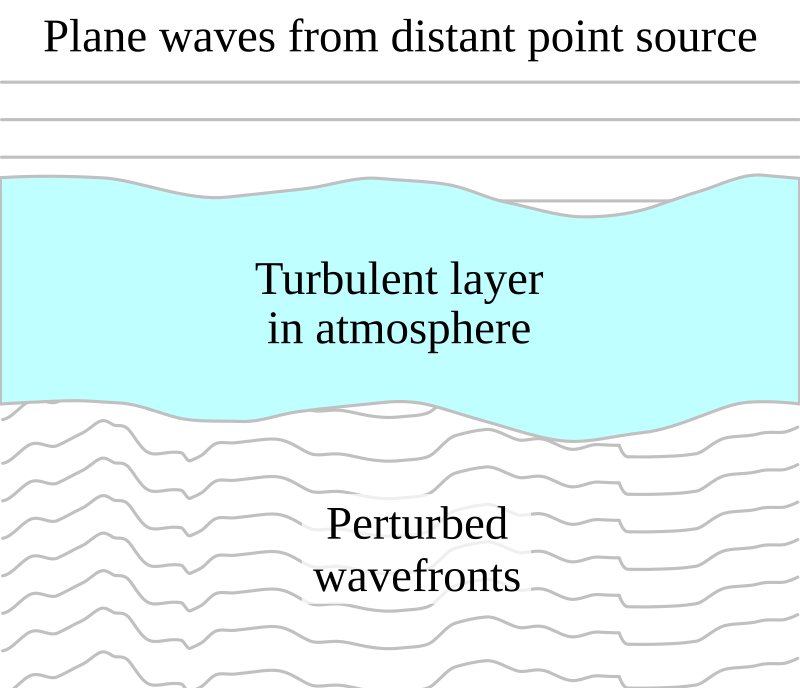

We observe stars that are far away because the light that they emit reaches our eyes (or telescopes). But in order to do that, it must first pass through the atmosphere. That means that light is indirectly subjected to phenomena that affect the Earth’s atmosphere.

Turbulence is a phenomenon that often happens on smaller scales. In the atmosphere, we have large-scale phenomena like cold fronts or hurricanes happening every day, but inside these events, turbulence is significant on a small scale. So cold fronts bring large thunderstorms, the clouds within the front can make the sky turbulent, and that’s when the airplane pilot tells you “Ladies and gentlemen, we’re experiencing some turbulence.”

There are several types of turbulence, including one called thermal turbulence — which happens when there is a mix between hotter and colder air. This could happen whether the sky is cloudy or not. When a mass of air in the atmosphere is hotter than its surroundings, it starts to rise, creating convective currents. Basically, you end up with moving columns or pockets of heated air that arise from warmer surfaces of the earth.

These moving pockets of air can create turbulence, and in the process, they also distort light that passes through them.

When it comes to stars, twinkling is caused by the passing of light through different layers of the turbulent atmosphere. This is more pronounced near the horizon than directly overhead since light rays near the horizon pass through denser layers of the atmosphere, but twinkling (technically called scintillation) can be observed on all parts of the sky.

But there’s more to this story.

Scintillation

When light passes through any medium (including the Earth’s atmosphere), some of it is reflected back, while some passes through the atmosphere, but at a different angle — something called refraction. When the atmosphere is turbulent in a region, the refraction angle is not constant, so light can change path quickly.

Altering the refractive index changes the apparent position of objects, just like the straw in a glass of water experiment, it looks bent. So the turbulent sky, constantly changing the refractive index makes stars appear to be moving, so they twinkle, or scintillate.

Due to scale differences, if an astronomical object is large enough compared to the turbulence, it won’t affect the way we see it. But the light of a smaller object (or one that’s farther away) will be affected as it crosses the turbulent air. That’s the reason why planets twinkle less (or almost don’t twinkle at all) — they are closer and it makes them ‘bigger’ compared to the turbulence.

Fortunately, atmospheric scientists developed a way to monitor changes in the refractive index of the atmosphere due to turbulence. They use instruments to measure the turbulence and use it to try to estimate a future outcome.

Different skies

For astronomers, twinkling can be quite problematic. So they look for the “best sky” to avoid the phenomenon. Usually, this means an environment whose climate is very dry. When that’s not possible, they try to find the dryness by placing the instruments at a high altitude. Whenever is possible to combine altitude and mostly dry weather, they have a good spot for a telescope.

In the images above we see the difference very clearly: both skies were clear when the images were taken, but one (on the left) was more turbulent than the other (on the right). On the left, we see a video of a star recorded on Mount Fuji in Japan — the star appears to be bouncing chaotically due to a turbulent sky. On the right, we see a recording of the same star taken on the Andes Mountains in Chile, a very dry, high-altitude area; the star bounces, but much less than in the Japanese images.

So stars don’t exactly twinkle, but they do appear to twinkle from here on Earth. For astronomers, though, making sure they eliminate the “twinkling” is important.

Of course, if you set your telescopes in space, you don’t have these problems because your observation point is above the atmosphere. But even here on Earth, astronomers are careful to pick the best locations for placing large optical telescopes. They typically look for the driest areas, at the highest altitude possible, without any light pollution. There’s another consideration: because the air is usually flowing from west to east because of Earth’s rotation, a way to avoid pollution is placing telescopes on west coasts or in ilands in the middle of the ocean. This rules out the vast majority of places on Earth, which is why astronomers are so particular about where they place their telescopes.