In a couple of ways, the planet called HD 63433 d is like Earth. It’s almost exactly the same size as the Earth, and it also orbits a star that’s similar to the Sun. But that’s where the similarities end.

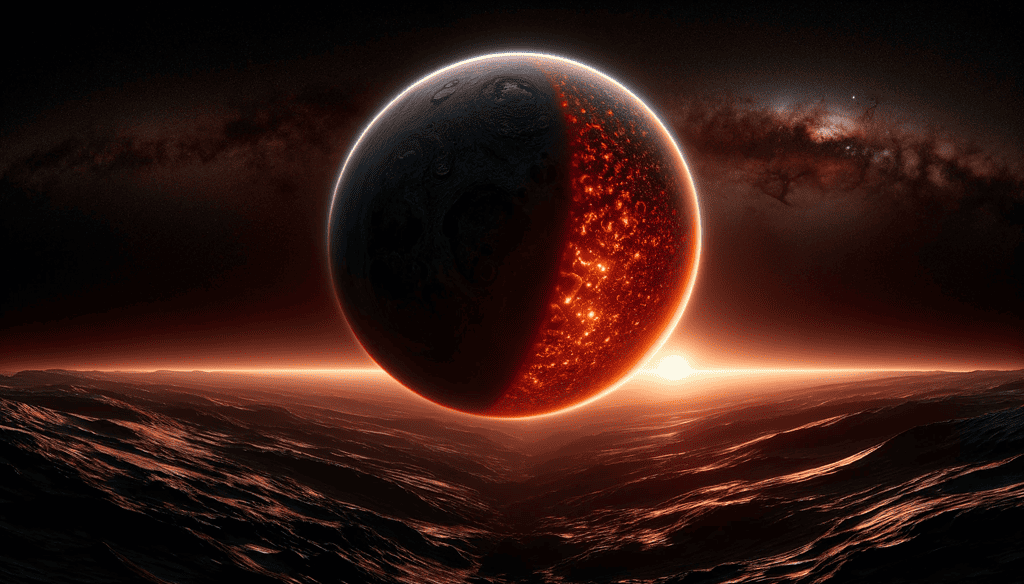

HD 63433 d is young for a planet, just 400 million years old (compared to Earth’s 4,500 million years). It’s also tidally locked, meaning the same side of the planet always faces its star, much like we only see the same side of the moon from Earth. It’s also much closer to its star — so close that the hemisphere that faces the star is probably covered in lava.

A hot, young planet

There are all sorts of planets in the universe. From planets as big as Jupiter but much hotter (rather unceremoniously called “Hot Jupiters”) to rocky, Earth-sized planets and Neptune-style water worlds, there’s no shortage of planetary diversity. It only makes sense that there are a few lava worlds out there; but it’s still amazing to discover them.

What makes it so hot is its proximity to its star. The star is a “G-type” star, just like our Sun. But HD 63433 d is so close to its star that its year only lasts for 4.2 days. It’s about 8 times closer than Mercury is to the Sun. That already makes it scorching hot. But the fact that it’s tidally locked makes things even worse on the close hemisphere.

If you’ve ever wondered why it is that there is a “near” and a “far” side of the moon, it’s because of a phenomenon called tidal locking, and this phenomenon isn’t as rare as you may think.

Tidal locking and lava

Tidal locking is a phenomenon that occurs when an astronomical body, such as a moon or planet, has its rotation period synchronized with its orbital period around a partner, typically resulting in the same face of the astronomical body always facing the partner. This happens due to the gravitational forces between the two objects, where the stronger gravitational pull of the larger body (like a planet on its moon) causes the smaller body to gradually slow down its rotation.

Over time, the rotational period of the smaller body matches its orbital period, leading to a state where one hemisphere perpetually faces the partner while the other faces away. This effect is fairly common and plays a significant role in the dynamics of planetary systems.

If the planet was spinning, the two hemispheres would have largely the same temperatures. But as one side is constantly facing the star, it’s perpetual day on one side and perpetual night on the other — and the day side is very, very hot.

NASA researchers estimate that the day side of HD 63433 d can reach temperatures of about 2,294 degrees Fahrenheit (1,257 °C ). That’s about as hot as the hottest lava on Earth and probably hot enough to melt whatever rock is on the planet’s surface. So basically, the planet is half lava.

Dips in luminosity

Astronomers discovered the planet by using the TESS telescope.

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is a NASA-led space mission launched in April 2018, designed to discover thousands of exoplanets orbiting nearby stars. TESS uses an array of wide-field cameras to monitor over 200,000 of the brightest stars near the sun for periodic dips in brightness. These dips are indicative of planets passing in front of their host stars, known as transits, which allow astronomers to infer the existence of a planet.

TESS’s primary mission is to identify terrestrial and larger planets in the habitable zones of their stars, where conditions might be right for life — but, of course, sometimes it finds planets like HD 63433 d, too. Unlike the Kepler mission, which focused on a small area of the sky, TESS scans the entire sky, making it possible to study the mass, size, density, and orbit of a large cohort of small planets, including a number that could potentially harbor life.

Even though the odds of this planet hosting life are astronomical, researchers still want to explore it in more detail. Follow up studies will focus on the dark side of the planet and its possible atmosphere. The reason why astronomers are so interested in it is because it’s so young that it can be used as a hotbed for testing theories on planetary formation and evolution.

The study was published in The Astronomical Journal.