In 2015, the Kepler Space Telescope found a pretty interesting planet. The planet, called K2-18 b, was thought to be a mini-Neptune orbiting a red dwarf (smaller than the Sun), some 134 light years away. Astronomers describing the finding noted that it could be a rocky world and that it’s 9 times more massive than Earth. They also mentioned that it “may be an interesting target for atmospheric studies of transiting exoplanets.”

How right they were!

Fast forward to 2023, and NASA puts out a press release of a JWST (James Webb Space Telescope) study, saying that the planet “could be a Hycean exoplanet, one which has the potential to possess a hydrogen-rich atmosphere and a water ocean-covered surface.” That’s pretty cool, but several media reports jumped the gun and speculated about JWST finding signs of life.

For now, that’s nothing more than speculation.

Water and life

Water is our best link to life as we know it. Without water, life can’t exist (or we don’t think it can exist). Water also can only exist under very specific temperature conditions. So, researchers are first looking for planets that fall within the temperature range that can support water; then they’re looking for signs of water itself.

So, what’s the deal with the mini-Neptune K2-18 b?

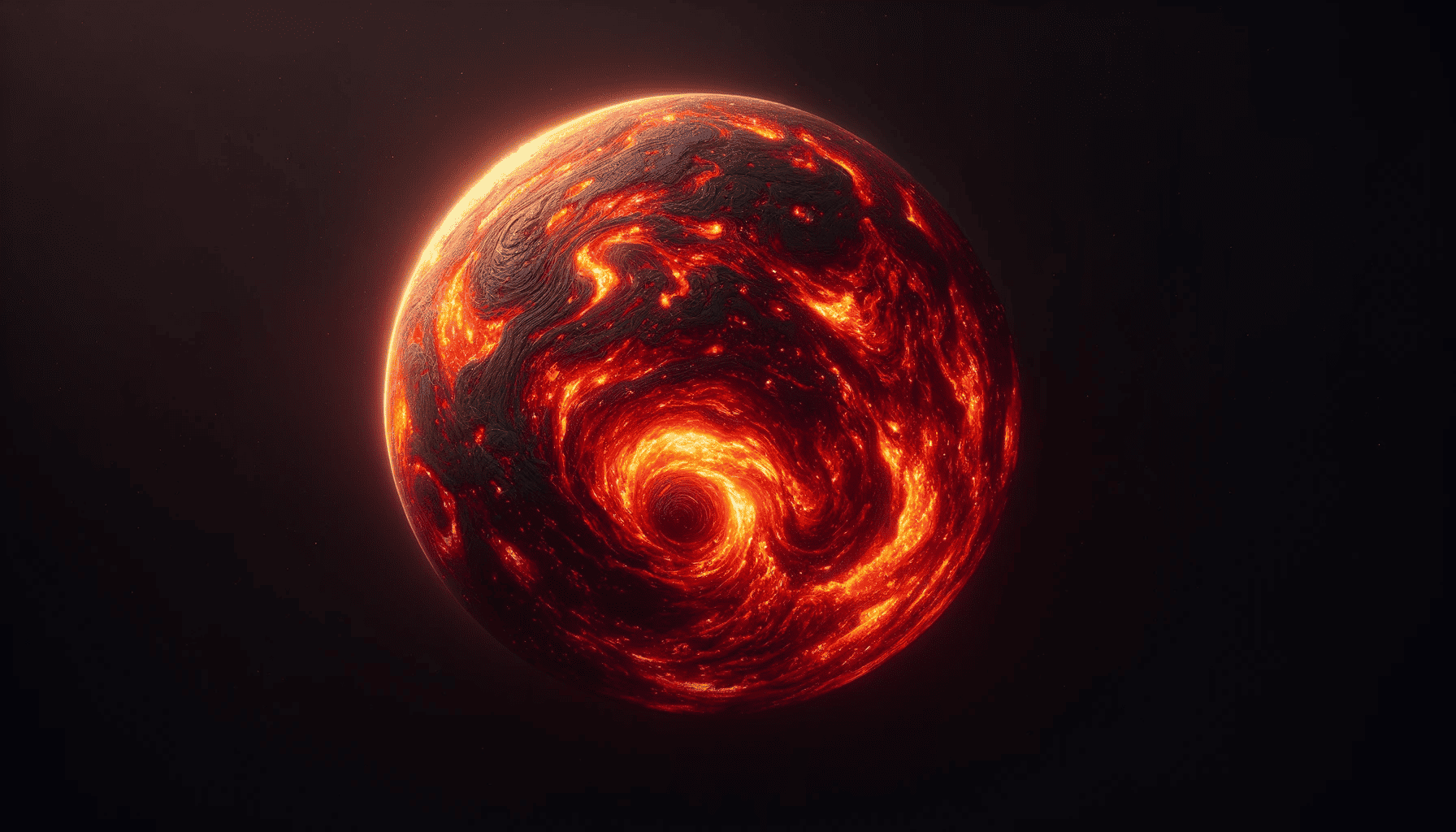

Well, the previous study concluded that K2-18 b probably has oceans. “Probably” because it’s really hard to tell with our current technology whether something so far away really has oceans. Also, oceans don’t necessarily mean water. In fact, the paper is titled “Distinguishing oceans of water from magma on mini-Neptune K2-18 b,” so oceans of lava are another possibility.

Even with the new JWST observations, K2-18 b is still quite a puzzle. Its density is somewhere between Neptune’s and Earth’s and we’re not really sure what it’s made of. In fact, it could have a range of different compositions. The most important clue that JWST brings is that it has an atmosphere that’s rich in carbon and poor in ammonia. These observations both fit with the idea of an ocean world with a thick hydrogen/helium atmosphere.

But they also fit with the idea of a magma world.

“We demonstrate that atmospheric NH3 depletion is a natural consequence of the high solubility of nitrogen species in magma at reducing conditions, precisely the conditions prevailing where a thick hydrogen envelope is in communication with a molten planetary surface,” the authors of the previous study write. So, we may very well be observing oceans of lava instead of water.

No signs of life?

So far, the planet is pretty intriguing. It definitely warrants further study. But what really stirred the discussion was the appearance of several media reports, especially the British news magazine The Spectator, which published an article titled “Have we just discovered aliens?” The article mixed in a bit of speculation, took a couple quotes out of context, and suggested that we may be well on the way to finding aliens — if we haven’t already.

But if you want a clue about just how taken out of context this is, here’s a tweet from Dr. Becky Smethurst, one of the people quoted in the article, about how she disagrees with the article’s perspective.

So, at the end of the day, neither NASA nor ESA, not JWST nor any other observatory or organization has found signs of aliens — and K2-18 b is definitely not in the discussion.

However, this being said, K2-18 b is really interesting for different reasons.

Back to actual science: Hycean exoplanets

Any planet that can potentially host water is interesting, as we explained earlier. But if K2-18 b actually has water, that makes it a part of a special class of hypothetical planets.

Hycean planets are water worlds that have a hydrogen atmosphere (HYdrocen oCEAN planets). Characterized by vast, deep oceans covering the entire surface and a thick, hydrogen-rich atmosphere, these planets are larger and warmer than Earth but smaller than ice giants like Neptune. Hycean planets are thought exist in a wide range of conditions, from those with moderate temperatures to those with more extreme environments. Their oceanic nature combined with hydrogen-dominated atmospheres makes them particularly intriguing for astrobiologists, as these conditions could potentially support microbial life forms, similar to extremophiles found in Earth’s most inhospitable environments. But researchers haven’t really confirmed that this type of planet exists. This is why K2-18 b is important, because it can show us whether this type of planet actually exists.

“Our findings underscore the importance of considering diverse habitable environments in the search for life elsewhere,” explained Nikku Madhusudhan, an astronomer at the University of Cambridge and lead author of the paper announcing the JWST results. “Traditionally, the search for life on exoplanets has focused primarily on smaller rocky planets, but the larger Hycean worlds are significantly more conducive to atmospheric observations.”

However, for that to happen, astronomers need to first figure out whether the oceans are indeed water — or lava. In order for that to happen, we need more data and more observations.

“Developing clear disambiguating atmospheric tracers for the presence of liquid water versus magma oceans is key in our quest of finding potentially habitable worlds among the exoplanet population,” the 2023 study authors conclude.