You may think that cold water therapy is a new trend, but people in the historic spa city of Bath, UK, were enjoying the therapeutic benefits of cold water over 200 years ago.

Archaeologists working on a historic building called the Bath Assembly Rooms discovered the cold water spa, equipped with “convenient dressing-rooms,” billiards, coffee and gambling spaces.

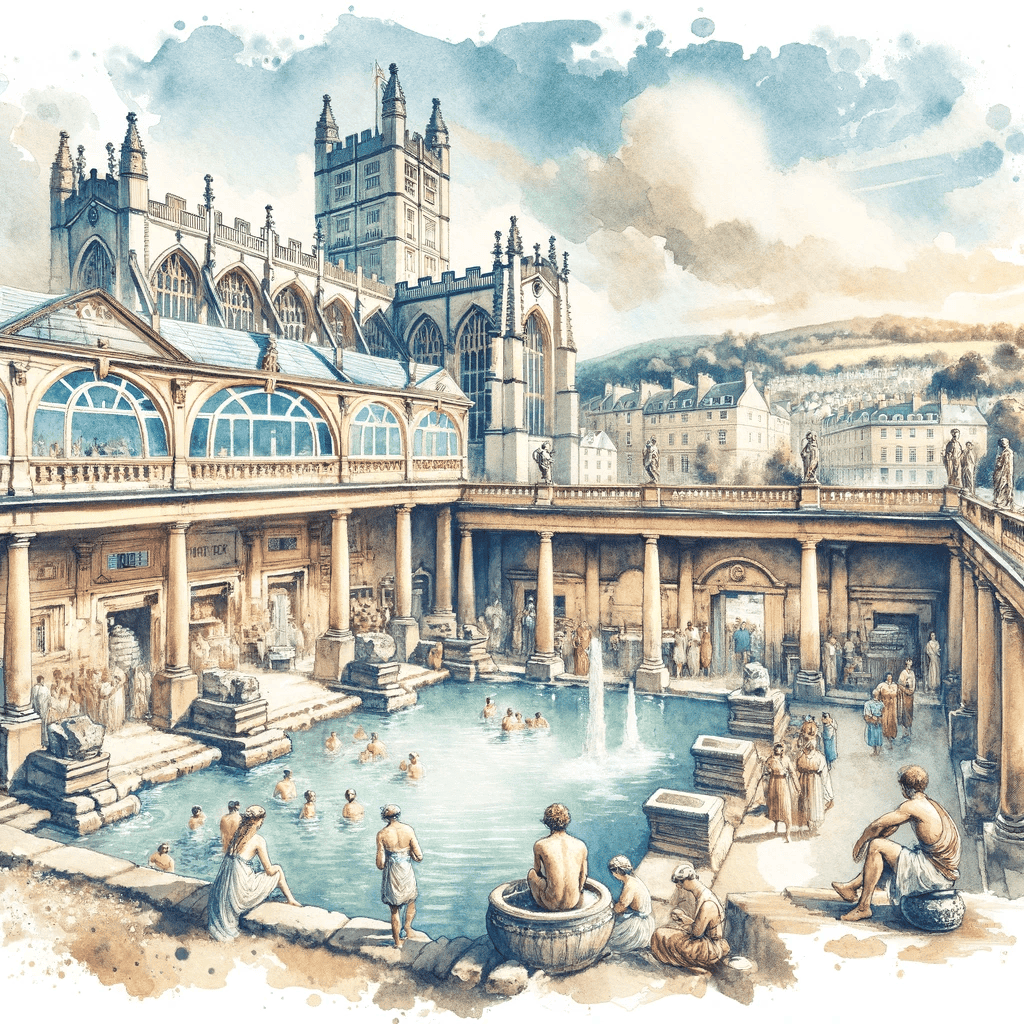

The city of Bath in England is named after the Roman-built baths that are one of its most famous attractions. The city was known as “Aquae Sulis” during Roman times, which translates to “the waters of Sulis.” Sulis was a local Celtic goddess whom the Romans equated with their own goddess Minerva. The Romans built a complex of baths and a temple around the hot springs found in the area, believing the waters had healing properties.

After the Romans left Britain, the baths fell into disrepair but the area continued to be known for its springs. The name “Bath” became more commonly used in the medieval period, directly referring to the bathing complex that had made the city famous. By the 7th century, Bath had become a religious center, and was only rebuilt as a large spa town in the 16th century. Not long after, claims were made about the curative properties of water from the springs, and Bath became popular as a spa town in the Georgian era.

The Bath Assembly Rooms were built around 1770, and would have been influenced by medical theories of the time. Specifically, the belief that cold water can alleviate an number of health conditions. But this wasn’t just a place to jump into cold water — it was a fancy and well-equipped spa facility.

Archaeologists digging at the site excavated tons of rubble and found finely joined stone walls that would have held statues or sculptures. They also found dressing rooms, as well as rooms where people could enjoy coffee and gamble. Yes, in the 18th century. There was even a place where people could play billiards, presumably after the cold bath, to warm themselves up a bit.

Researchers had some idea that the spa bath was there, but as the building was bombed during World War II.

Tatjana LeBoff, National Trust Project Curator, explained:

“There are many elements of this discovery that are still a mystery. The Cold Bath at the Assembly Rooms is highly unusual. It is a rare, if not unique, surviving example, and possibly it was the only one ever built in an assembly room.”

“Whilst our records tell us about a variety of people who were employed at the Bath Assembly Rooms in the 1770s, none of the records mention anyone being employed to attend the Cold Bath. Nor are there records of bath sheets being hired or bought or any laundry service for them, so perhaps the bather would have brought their own towels and servant to help with bathing and dressing.

“It is unlikely men and women of status would have used the Cold Bath together so there could have been different days or times when they were available to each. We are still researching records, letters, diaries and other documents to see what more we can find out that will help us piece it all together.”

It’s “tremendous” to be able to piece together this rare archaeological evidence, says Bruce Eaton, Archaeologist at Wessex Archaeology, who worked on the project. The finding is important because it sheds light on the social interactions of the time.

Oftentimes, modern archaeology is not just about finding things — but figuring out how people at the time lived, by studying the things. The Cold Bath at the Bath Assembly Rooms is just that: a window into the past that allows us to understand the complexities of Georgian-era social and medical practices.

As researchers continue to dig through historical records and the physical site, they hope to uncover more about how this unique facility was used and by whom. The find not only enriches our understanding of Bath’s long-standing relationship with spa culture but also challenges our modern perceptions of wellness and social interaction, reminding us that the quest for health and community is indeed timeless.