Facebook communities that promote distrust in ‘the establishment’ and official health guidelines are more effective than reliable health groups at reaching and engaging with undecided individuals, a new study reports.

The study was carried out at George Washington University and used a special tool built to track vaccine discussions on Facebook during the 2019 measles outbreak. This “battleground” map reveals the broad dynamics of how distrust in established guidelines is fomented on social media. The authors caution that this distrust can come to dominate public discourse in the future, which would pose a major block against immunization efforts for COVID-19 and future outbreaks.

In strangers on the Internet we trust

“There is a new world war online surrounding trust in health expertise and science, particularly with misinformation about COVID-19, but also distrust in big pharmaceuticals and governments,” says Professor Neil Johnson, lead author of the paper.

“Nobody knew what the field of battle looked like, though, so we set to find out.”

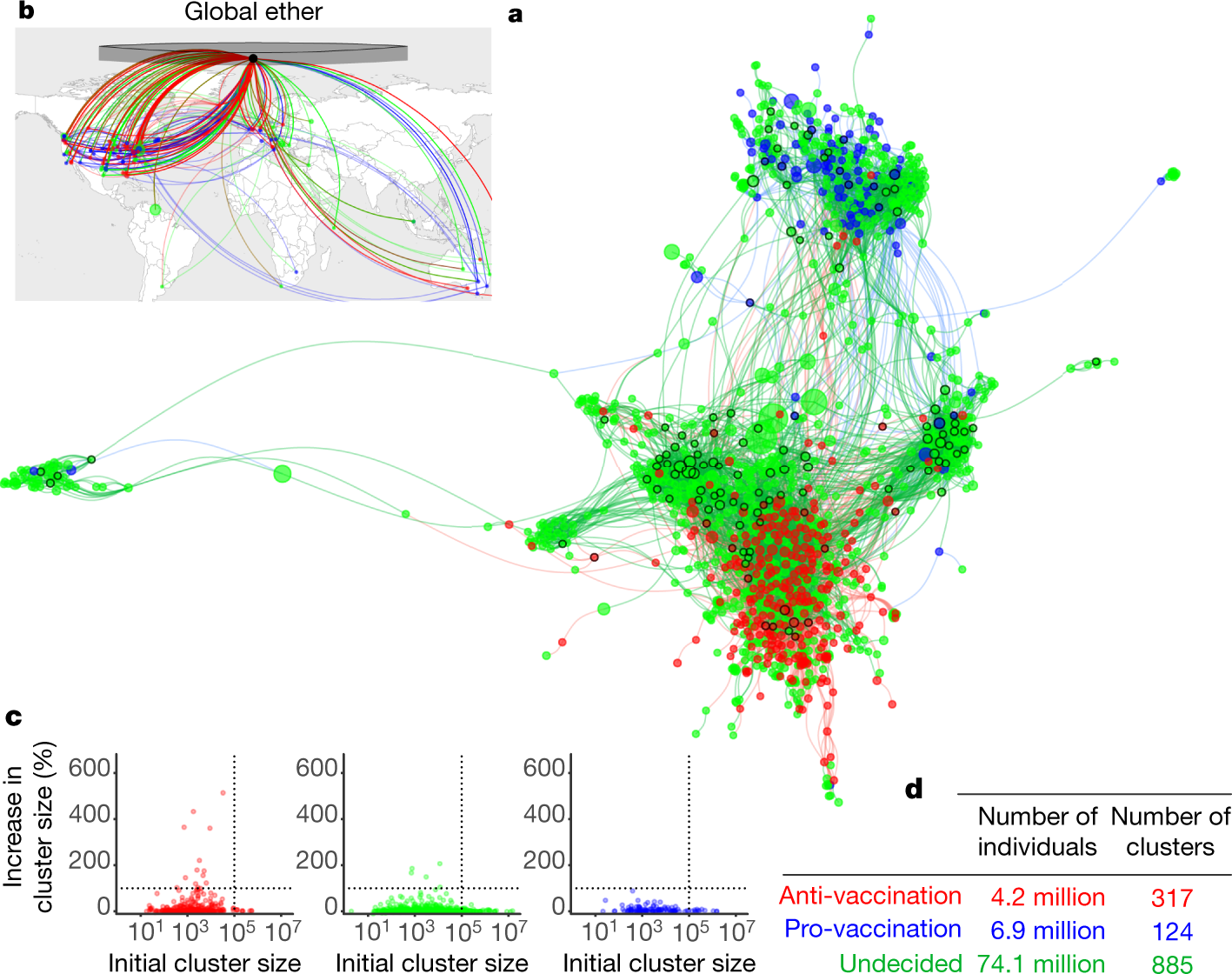

The team examined several Facebook communities totaling almost 100 million individual users. These groups, they explain, formed a dynamic and highly-interconnected network that spanned across national borders and cultures.

Among these groups, three ‘camps’ were identified: pro-vaccination, anti-vaccination, and those of “undecided” individuals (for example, parenting groups which discussed vaccines but didn’t lean either way). The team started with a certain community and would then find another one that had strong links to it, repeating the process until they reached a better understanding of the overall relationships forming among the communities.

Image credits Neil F. Johnson et al., (2020), Nature.

They report that overall, there are fewer individuals who agree with anti-vaccination sentiments than with pro-vaccination on Facebook, but there are almost three times as many anti-vaccination communities on this platform than pro-vaccination ones.

The anti-vaccination users utilize these groups to engage with undecided communities, while the pro-vaccination ones keep largely to themselves. They focused their efforts on countering the larger anti-vaccination groups, which left the smaller splinter-groups pretty much free to operate with impunity.

Furthermore, while the pro-vaccination camp understandably sticks to one creed (“vaccines work and they’re safe”) their opponents can have their pick of narratives and use this to engage with the undecided. These range from promoting safety concerns or individual choice to conspiracy theories, which they tailor to the particular community they’re addressing at the time.

The team notes that individuals in the undecided communities tended not to sit idly, but were actively engaging with the vaccine content. “The undecided clusters have the highest growth of new out-links [i.e they’re actively engaging with the other two groups] followed by anti-vaccination clusters,” the paper reads.

“We thought we would see major public health entities and state-run health departments at the center of this online battle, but we found the opposite. They were fighting off to one side, in the wrong place,” Dr. Johnson said.

Social media often works to amplify and equalize information, the team explains, meaning it makes it readily accessible but also gives different opinions the appearance of being equally worth considering (they’re not).

The team proposes several strategies to better combat the spread of misinformation on social media such as influencing the heterogeneity of individual communities (making them more diverse) to delay radicalization and decrease their growth, as well as manipulating the links between communities in order to prevent the spread of negative views.

“Instead of playing whack-a-mole with a global network of communities that consume and produce (mis)information, public health agencies, social media platforms and governments can use a map like ours and an entirely new set of strategies to identify where the largest theaters of online activity are and engage and neutralize those communities peddling in misinformation so harmful to the public,” Dr. Johnson said.

The paper “The online competition between pro- and anti-vaccination views” has been published in the journal Nature.