Quantum entanglement and other quantum phenomena have long been suspected by scientists to play a role in chemical reactions like photosynthesis. But, until now, their presence has been hard to identify.

Researchers at Purdue University have unveiled a new method that enables them to measure entanglement — the correlation between the properties of two separated particles — in chemical reactions.

Discovering just what role entanglement play in chemical reactions has implications for the improvement of technologies like solar energy systems if we can learn to replicate them.

The study — published in the journal Science Advances — takes the theorem ‘Bell’s Inequality’ and generalises it to identify entanglement in chemical reactions. In addition to theoretical arguments, they also performed a series of quantum simulations to verify this generalized inequality.

Sabre Kais, a professor of chemistry at Purdue, explains further: “No one has experimentally shown entanglement in chemical reactions yet because we haven’t had a way to measure it. For the first time, we have a practical way to measure it.

“The question now is, can we use entanglement to our advantage to predict and control the outcome of chemical reactions?”

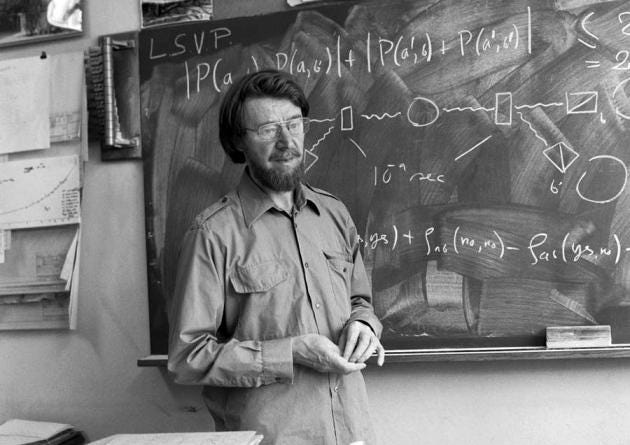

Bell’s Inequality — identifying entanglement.

Since its development in 1964, Bell’s Inequality has been validated as the go-to test that physicists use to identify entanglement in particles. The theorem uses discrete measurements of properties of particles such as the orientation in their spin — nothing to do with angular momentum in the quantum world — to find if the particles are correlated.

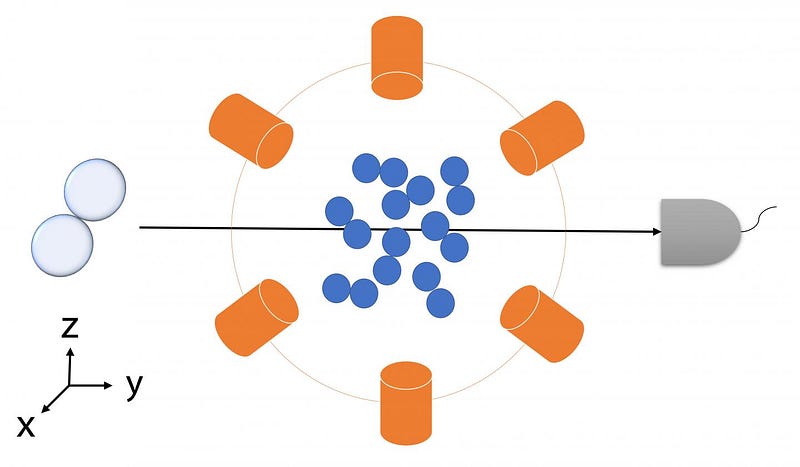

The problem is, discovering entanglement in chemical reactions requires that measurements are continuous. This means measuring aspects such as the angles of beams which scatter reactants forcing them into contact and transform into products.

To combat this, Kai’s team generalised Bell’s Inequality to include continuous measurements in chemical reactions, in a similar way to how the theorem had previously been generalised to examine light — photonic systems.

The team then tested their generalised Bell’s inequality using a quantum simulation of a chemical reaction yielding the molecule deuterium hydride.

The process was built on a foundation established in a 2018 experiment developed by Stanford University researchers that aimed to study the quantum states of molecular interactions.

Because the simulations validated the Bells’s theorem and showed that entanglement can be classified in chemical reactions, Kais’ team proposes to further test the method on deuterium hydride in an experiment.

Kais says: “We don’t yet know what outputs we can control by taking advantage of entanglement in a chemical reaction — just that these outputs will be different.

“Making entanglement measurable in these systems is an important first step.”