New research from the Egypt Centre at Swansea University in the UK is shedding light on the lives — and after-lives — of Egypt’s ancient pets.

Image credits Richard Johnston et al., (2020), Scientific Reports.

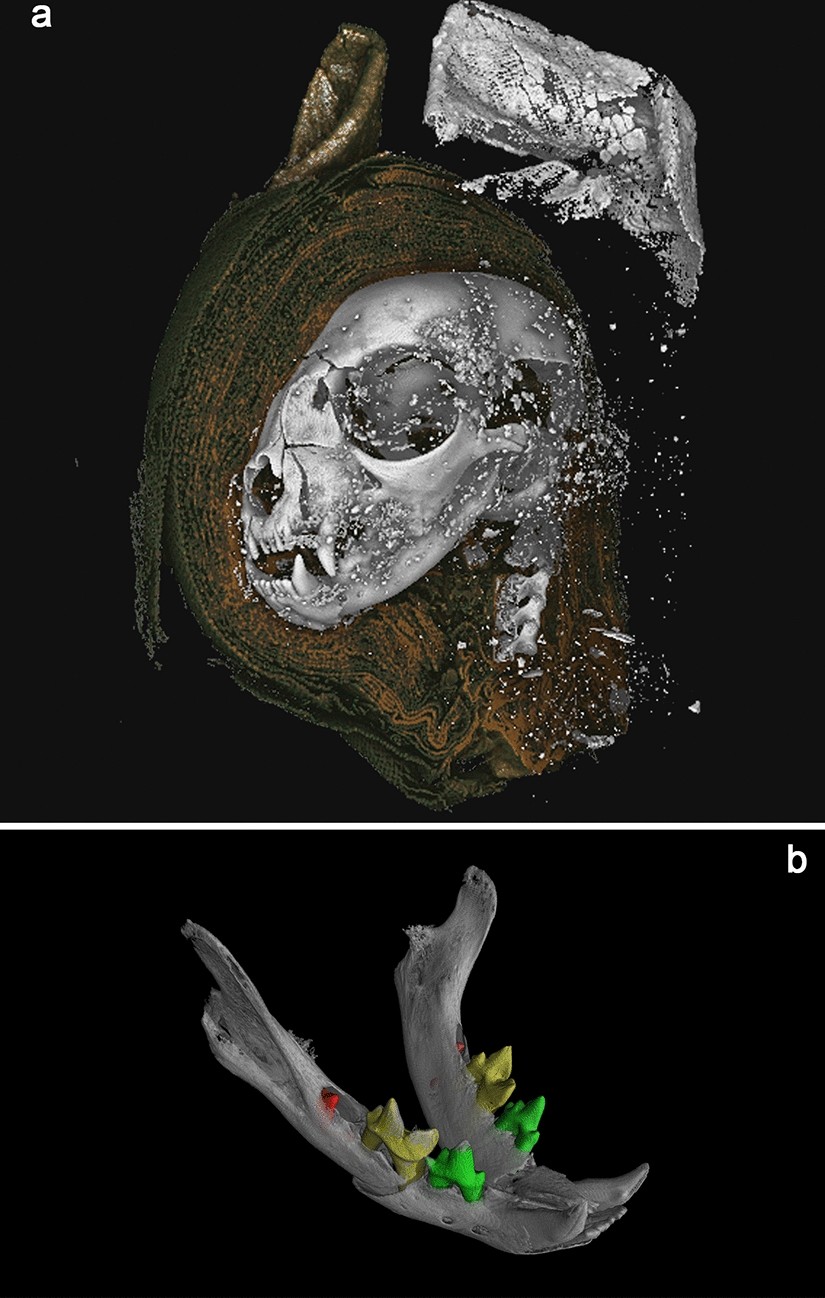

The team generated 3D models of a mummified snake, bird, and cat from the University’s collection. The method they employed — X-ray micro CT scanning — is extremely accurate, creating images with 100 times the resolution of a medical CT scan. The findings help us better piece together the lives and deaths of Egyptian animals, and offer us a glimpse into the culture of these ancient peoples.

Although these aren’t fossils, the techniques used here can be adapted to the study of fossils. The results also look spectacular — so I’m going to give them an honorary place on Fossil Friday.

Together forever

“Using micro CT we can effectively carry out a post-mortem on these animals, more than 2000 years after they died in ancient Egypt,” says co-author Dr. Carolyn Graves-Brown from the Egypt Centre at Swansea University.

“We were able to piece together new evidence of how they lived and died, revealing the conditions they were kept in, and possible causes of death. These are the very latest scientific imaging techniques. Our work shows how the hi-tech tools of today can shed new light on the distant past.”

Previous research has focused on the outside of these mummies as any direct intervention inside risked destroying them beyond repair. We knew which animals they likely were, but not much else. The digital approach allows us to investigate their insides without damaging them. Methods such as X-ray or CT scanning have been available for some time, but they are limited in usefulness: the first only returns 2D images, and the latter has comparatively poor resolution.

The team employed micro CT because it can produce high-quality, 3D images. The process is most commonly used in materials science and constructs the 3D image by layering multiple 2D scans.

They report that the mummified cat was no older than 5 months, as suggested by unerupted teeth in its jaw bone. Due to separation of vertebrae in its neck, they say that the most likely cause of death was strangulation. The bird is a close match for a Eurasian kestrel, and the snake was identified as a juvenile Egyptian Cobra.

Image credits Richard Johnston et al., (2020), Scientific Reports.

The snake shows some signs of kidney damage and gout, probably due to lacking water during its life. It was likely killed by whipping (against a hard surface) as evidenced by bone fractures in its skull and neck. The team says this is the earliest evidence of a complex ritual (mummification) being performed on a snake.

The bird, meanwhile, seems “superficially intact”, the team notes. There is some evidence of damage to its beak and left leg, but this was likely caused after mummification.

So what did these poor animals do to deserve such a treatment? Well, ancient Egyptians had a habit of mummifying animals as well as people. Cats, ibis, hawks, snakes, dogs, and even whole crocodiles have been found mummified. Sometimes these were pets, but most often, they were messengers to the gods. These animals, it was believed, could act as intermediaries between mortals and their gods.

Not all of them were wild animals — most were in fact bred in captivity. It’s estimated that as many as 70 million animals were probably mummified this way.

The paper “Evidence of diet, deification, and death within ancient Egyptian mummified animals” has been published in the journal Scientific Reports.