Every year, billions of people all around the world celebrate Christmas and have no idea where this festival came from.

Christmas draws from Roman and druidic celebrations. The roots of Christmas are in ancient events like Saturnalia to the German celebrations of Yule, which served the Norse god Odin. Christmas actually comes from pagan celebrations and fertility rites. In fact, Christmas is really about “bringing out your inner pagan,” some historians say.

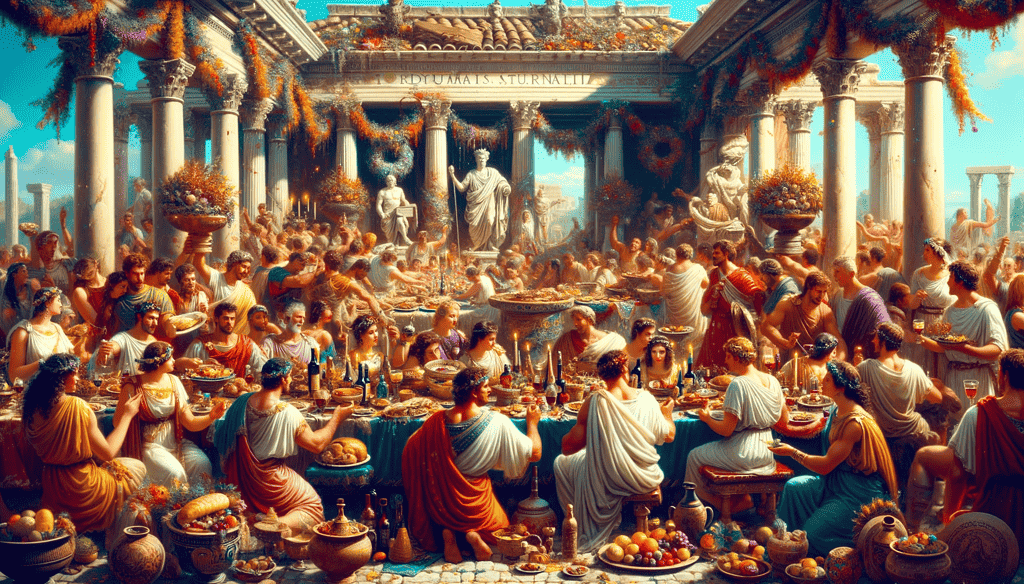

Christmas before Christ — the Roman Saturnalia

For most people, Christmas is a holiday deeply rooted in Christianity. But Christmas has less to do with Jesus and Christians and more to do with pagan celebrations in temples.

The ancient Romans celebrated the winter solstice, feasating and celebrating the god Saturn (the equivalent of Zeus). Other cultures, like the Celts, had their own version of celebration around the same period.

The earliest history of Christmas is composed of “pagan” (non-Christian) fertility rites and practices that predate Jesus by centuries. Most of the traditions we associate with Christmas are actually not Christian at all. These traditions include decorating Christmas trees, singing carols, and giving Christmas gifts. Yes, all those beloved Christmas practices are not Christian at all.

So then, how did Christmas get to what it is today?

The origins of Christmas

Humans have celebrated Christmas (in one form or another) for more than two millennia. In that time, the customs we have today have become a mixture of different cultures and traditions.

But wait, isn’t Christmas when Jesus was born? The answer is almost definitely ‘no’. We really have no clear idea when Jesus was actually born. However, the most plausible dates (if Jesus did exist in fact) are not in December at all, and it’s possibly not in ‘year 0’ either.

The New Testament gives no date or year for the birth of Jesus. The first calculation we have came from Dionysius Exiguus, a Scythian monk, “abbot of a Roman monastery”. In the Roman, pre-Christian era, years were counted from ab urbe condita (AUC) — from “the founding of the City”, with the city being Rome. So 1 AUC is the year Rome was founded — what we now call 753 BC. The year 10 AUC signifies the 10th year after Rome was founded and so on.

Historian and monk Dionysius Exiguus based his calculations on Roman history and estimated that Jesus was born in 754 AUC. However, Luke 1:5 places Jesus of Nazareth’s birth in the days of Herod, and Herod died in 750 AUC. This is four years before the year in which Dionysius places the birth of Jesus. In fact, most researchers conclude that Jesus was born somewhere between 6 BC and 4 BC. Pretty much any way you take it, it seems very unlikely that Jesus was born in what we consider year 0.

Joseph A. Fitzmyer – Professor Emeritus of Biblical Studies at the Catholic University of America, member of the Pontifical Biblical Commission supports this idea:

“Though the year [of Jesus birth is not reckoned with certainty, the birth did not occur in AD 1. The Christian era, supposed to have its starting point in the year of Jesus birth, is based on a miscalculation introduced ca. 533 by Dionysius Exiguus.”

The date, 25th December, is even more dubious.

The date was first asserted officially as the birth of Christ by Pope Julius I in 350 AD. However, the pope didn’t really bring any evidence to justify his claim.

The influential Greek bishop Irenaeus (c. 130–202) had a different idea. Irenaeus thought that Christ’s conception was in March 25. This would be linked with Jesus being born nine months later on December 25. The Bible doesn’t speak about the date, but the references in the Bible show it most likely did not take place in winter.

It was actually pagan customs that brought the year of 25th December.

Romans and Christmas

Before Christians embraced this celebration, the Romans had Saturnalia.

Romans first introduced the holiday of Saturnalia, which was basically a week-long lawless celebration, taking place between December 17-25. During this period, the Romans closed their courthouses. In other words, the Roman law that normally dictated was halted. No one could be punished for damaging property or injuring people during the weeklong celebration. The things that happened during the Saturnalia were almost unspeakable – we won’t go into that here, but they often included violence, rape, and even human sacrifice.

Another interesting tradition was the pagan custom called wassailing, or singing from door to door. This is the beginning of Christmas caroling.

While the wealthy feasted and did their thing, the poorer people gathered and sang from door to door, with people often giving them food and (more rarely) drink. This custom continued throughout the Middle Ages and became established. It was also a common habit for people to gather in groups and sing naked in the streets – really, these are the precursors of caroling. So caroling, yet another favorite Christmas tradition, is also pagan in origin.

As the first few centuries of the “AD” era passed, Christians wanted to attract more pagans into their religions. They attempted to incorporate Saturnalia into Christianity. The only problem was that it had absolutely nothing Christian in it. So instead, they adopted its ending date (25th of December). Because Saturnalia was the biggest festival and celebration in ancient Rome, they had to make the date important as well, so they made it the birth of Jesus. It was a rather clever political trick. It took the existing religion and tradition and blended it with the new Christian rite.

Stephen Nissenbaum, professor of history at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, writes:

“In return for ensuring massive observance of the anniversary of the Savior’s birth by assigning it to this resonant date, the Church for its part tacitly agreed to allow the holiday to be celebrated more or less the way it had always been.”

So it’s very unlikely that December 25 and “year 0” are the actual birth of Jesus.

Christmas becomes Christian

The early Christians learned a lot from the Romans. Despite what most people today think, the Romans didn’t really invent much. But they were very adept at incorporating customs and practices from the places they conquered.

Early Christians tried to do the same, and they were also smart about it. They wanted to attract as many people as possible. But at the same time, they realized that the people weren’t giving up on the things they’d been doing for generations and generations. So instead, they tried to incorporate all these pagan traditions and make them a part of Christianity.

The best example for this is the one with the Saturnalia – but that’s nowhere near the only case. Just as early Christians recruited Roman pagans by associating Christmas with the Saturnalia, so too worshippers of the Asheira cult and its offshoots were recruited by the Church sanctioning “Christmas Trees” – but that’s a matter for a different article.

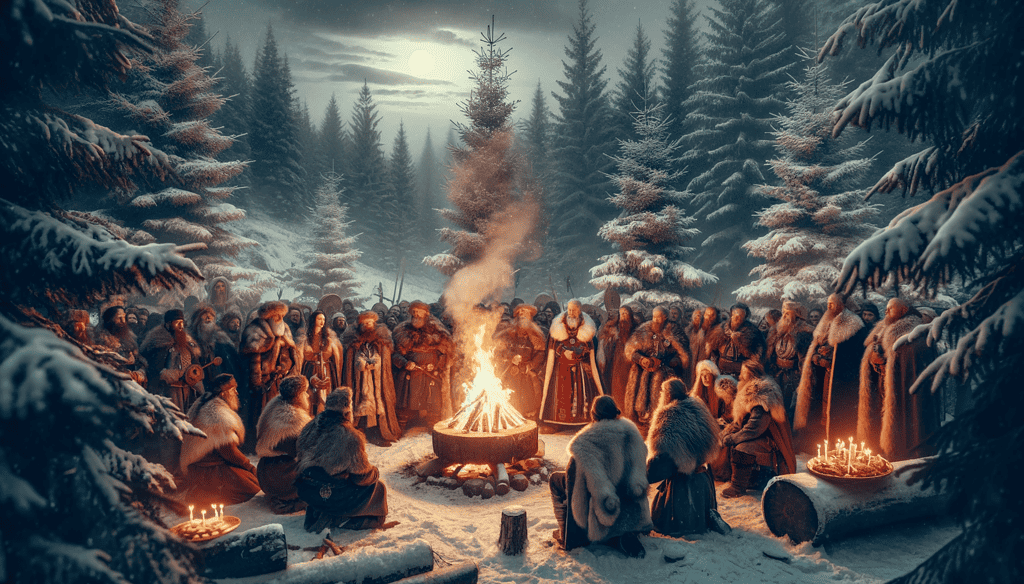

Yule celebrations

But just because Christians came along doesn’t mean other religions disappeared overnight.

Parallel to the Roman Saturnalia, the Northern European pagans celebrated Yule around the time of the Winter Solstice. This festivity involved speccific traditions. Notably, people burned the Yule log, feasted, and honored the gods to bring forth the rebirth of the sun. Yule was deeply embedded in the Germanic and Norse cultures. It reflected a reverence for the natural cycles of darkness and light.

Yule was the most prominent of the pagan celebrations associated with Christmas.

The Pagan traditions across various cultures celebrated the return of light after the year’s darkest period. This involved festivals of fire and light. These celebrations marked the Winter Solstice, the shortest day of the year, as a turning point. This solstice heralds the gradual increase of daylight. Fires and lights, central to these festivals, symbolized hope and the rejuvenation of life. This is a theme that resonates deeply with several human cultures.

Over the centuries, the term “Yule” got closer and closer to Christmas, especially in regions with a strong historical influence from Northern Europe. Many of the traditions that were once part of the ancient Yule celebration are now embedded in Christmas festivities. The burning of the Yule log, the use of evergreen decorations, and even aspects of the feasting and communal gatherings have been absorbed into the Christmas traditions we recognize today.

German celebrations, Odin, and Christmas

Odin, a major god in Norse mythology, also plays a role in Christmas. Known as the “Yule Father,” Odin was believed to lead a great hunting party through the sky during Yule. This event, often depicted with Odin riding his eight-legged horse Sleipnir, was a magical and ominous spectacle. Odin was also seen as a gift-giver. This trait would later influence the development of figures like Saint Nicholas and Santa Claus.

As Christianity spread into Germanic regions, the Church faced the challenge of converting pagan populations. Similar to what happened with Saturnalia in Rome, the Church sought to Christianize popular pagan festivals by aligning them with Christian celebrations. The midwinter festival of Yule, with its deep cultural significance, was a prime candidate for this.

Aspects of Odin’s persona were lated incorporated into Christian and secular customs. Saint Nicholas, a Christian bishop known for his generosity, became a key figure in Christmas celebrations. Over time, attributes of Odin merged with the lore of Saint Nicholas, evolving into the modern figure of Santa Claus. The transformation included elements like the nocturnal gift-giving and the magical journey through the skies.

Modern Christmas

In time, Christmas blended and morphed, adapted multiple cultures and customs. In fact, the integration of Germanic celebrations and the figure of Odin into Yule and Christmas is a prime example of cultural syncretism. This blending of beliefs and customs across different religions and cultures demonstrates the dynamic nature of cultural practices and how they adapt to changing religious and social landscapes.

The result is a holiday season that, while predominantly Christian in its current interpretation, still carries with it the echoes of ancient pagan rites and deities, a testament to the enduring nature of these early traditions.

Elements like the Christmas tree, Yule log, and even the image of Santa Claus traveling through the night sky are echoes of ancient Germanic and Norse practices. The story of Odin and the Yule festival lives on, transformed and repackaged within the framework of Christmas.

So when you’re celebrating Christmas, don’t just dismiss it as a Christian celebration or a consumerist invention. Christmas has undergone many changes and incorporates many different traditions and customs. It’s a complex celebration. After all, there’s a reason why it’s still the most popular celebration on the planet.