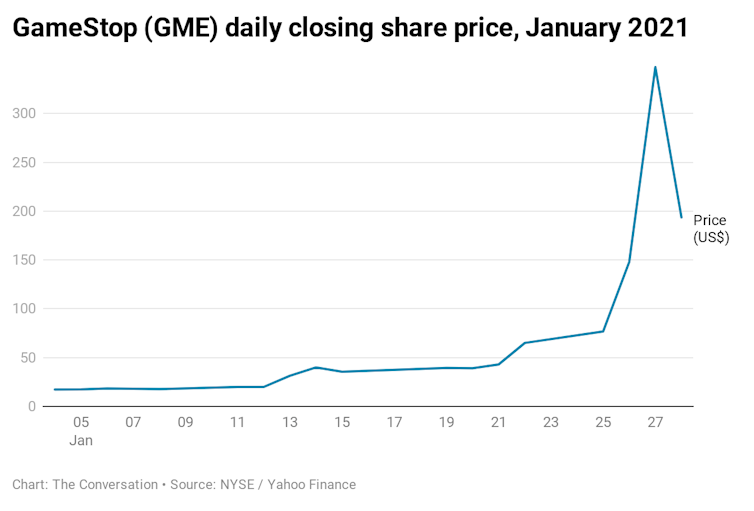

How does a small retail company that sells video games, worth less than US$400 million in the middle of 2020, become a US$10 billion company in less than six months? How does its share price climb from about US$20 on January 12 2021 to US$347 on January 27 – then fall back to US$193 the very next day?

The stunning price surge in GameStop shares, driven largely by hyped-up Reddit users with the aid of Elon Musk, has drawn the attention of the US government, led to calls for regulation from the head of the NASDAQ exchange, and even driven up the shares of an Australian mining company with a coincidentally similar sharemarket code.

How is this happening? The simple answer is it’s a power play, magnified by social media, between small retail investors who want some share prices to rise and larger hedge funds who have made big bets that those same prices will fall.

Revenge of the little fish

Melvin Capital is a hedge fund (worth US$12.5 billion until recently) with a “short position” on GameStop. A short position means Melvin was betting GameStop’s share price would fall (a reasonable bet, as the outlook for bricks-and-mortar video game stores is a bit like what happened to Blockbuster and other video rental outlets). This in itself is not at all unusual.

What made the past two weeks so unique was the heavy involvement of small individual investors in driving the action. Through platforms like Reddit (specifically the Wall Street Bets forum, which describes itself as “like 4Chan found a Bloomberg terminal”), these retail investors have worked to together to drive prices so high that hedge funds have had to abandon their short positions.

As a result, the short sellers have lost a lot of money and the retail investors (and anybody else with GameStop shares) have made huge profits. Normally on the stock market, the shark swallows the little fish. Now the little fish are eating the shark.

Read more: Explainer: what is short selling?

These individual investors started buying shares (and options to buy shares in the future) in GameStop, and other companies that had significant short positions. In fact, the 50 most shorted companies on the Russell 3000 index have gone up 33% this year.

This increase has become a surge in recent days. GameStop surged in value by 92% on January 26 (US time), leapt another 134% on January 27, and has traded more than 178 million shares. The average volume typically traded for GameStop is roughly 10 million shares per day. This is not normal.

How long can redditors remain irrational?

How is it possible that small retail investors can drive the value of a company up like this?

Two important factors have led to the situation. The first is structural. Investors seized on the fact that Melvin, and another fund called Citron Capital, had significant short positions in GameStop.

When a stock price surges, short sellers must either put in more money to sustain their position or liquidate it. Melvin tried to sustain its short position, because the hedge fund’s managers believe the stock is overvalued, and has suffered massive losses as a result (last week, Melvin announced it was already down 30% on the year). This is a case of the well-known idea that “the market can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent”.

Melvin may ultimately be right, and GameStop’s price will eventually fall, but retail investors who knew about Melvin’s bet forced it into an untenable position. With the price continually pushed up, Melvin was left with a stark choice: continue to go short, or else realise its losses.

How buying creates more buying

This leads to the second factor, which is mechanical. The retail investors driving the price surge are much smaller than the hedge funds they are battling. By buying the stock and call options (which are effectively rights to buy the stock in future at a certain price), retail investors are causing market makers to also buy shares in GameStop.

Market makers are companies that facilitate share trades by owning stocks and making them available for sale. Market makers don’t care about whether stock prices rise or fall; they just want a cut when people buy or sell.

So when an investor buys a call option from a market maker, the market maker will immediately hedge the position by buying the stock. This way, they are covered whether the price rises or falls.

If there is a big enough surge in speculators buying call options, as we have seen with GameStop, it will be accompanied by a lot of stock buying.

This is a cascading effect, which leads to price runs. In this case, it’s running the price up, but we are just as likely to see the same effect running the price down as well. (This is what happened on a larger scale on October 19, 1987, triggering the Black Monday stock market crash.)

After the surge

These two factors – short sellers getting squeezed and market makers hedging their bets – have led to this situation. You need both for what we are witnessing: an investor with an exposed position (Melvin) and a flurry of investors targeting that position (Redditors and others).

Soon this will be all over. Late on January 27 (US time), Melvin Capital announced it had abandoned its short position. It’s unclear how much money Melvin lost, but it has taken on almost US$3 billion in investment from the Citadel and Point72 funds to cover its losses.

The next morning, GameStop’s price actually continued to rise, reaching almost US$500 for a brief moment. However, at that point several popular retail stockbrokers – including Robinhood, Interactive Brokers and E*Trade – intervened to limit trading in several highly active stocks including GameStop. The price quickly plummeted before rallying and ending the day at $US193.60.

What’s next? With the short sellers removed from the game, the reality of the company’s business prospects may reassert themselves.

The past two weeks have been exciting times for market watchers. But we cannot ignore the apparent ease with which these stocks have been manipulated, and the possibility of more market manipulation in the future.

James Doran, Associate professor/Deputy head of school, UNSW

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.