The initial career of Jean Baptiste Vérany focused on pharmacy. But the 19th-century Frenchman soon found his attention drawn to something else: the sea. Specifically, Vérany was interested in cephalopods.

The story starts when Vérany embarked on a research expedition with Franco Andrea Bonelli, a preeminent ornithologist and entomologist. This expedition spurred Vérany’s interest in zoology and he never looked back.

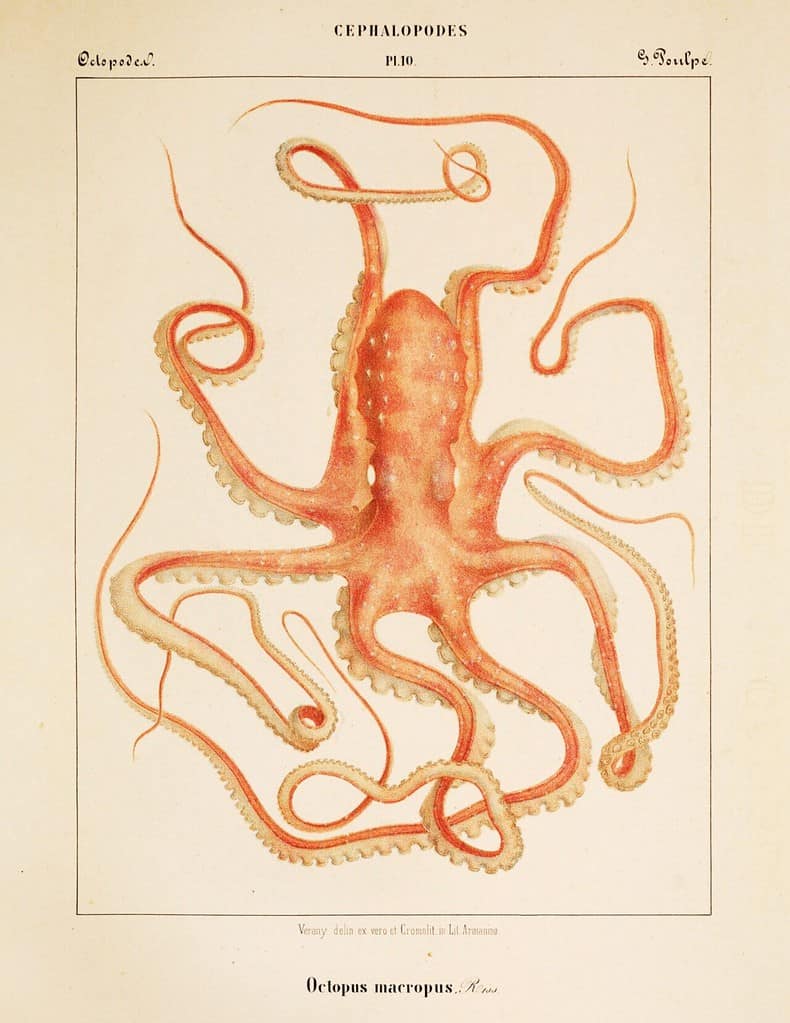

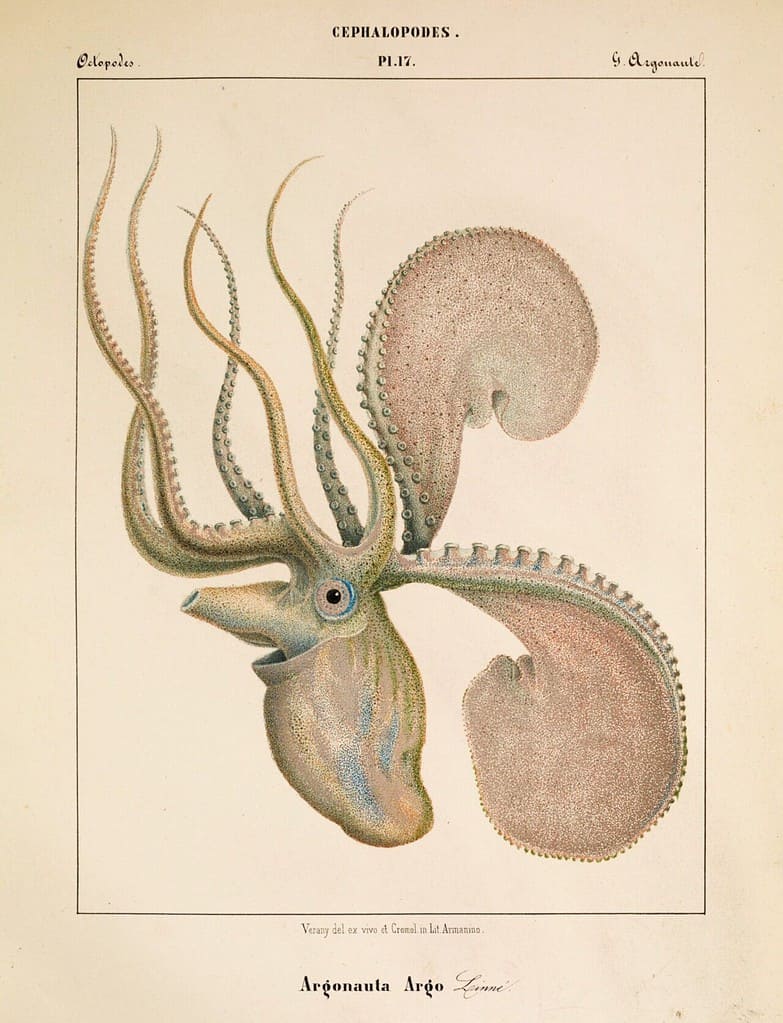

A stunning collection of cephalopod art

Born in Nice, France, Vérany had a draw towards marine creatures. By 1834, he was already focusing on the study of cephalopods — a group that includes eight-armed octopuses, the eight-armed and two tentacled squids and cuttlefishes, and the shelled chambered nautiluses.

He had already started publishing some notable art. In particular, one depiction did a great job at highlighting the subtle, shifting shade of the cephalopod skin. Even now, the chromatophores that shift the octopus’ colors are poorly understood; back then, they were largely mysterious.

Things really took off in 1851 when Vérany would go on to publish a collection of illustrations. Mollusques méditeranéens: observès, decrits, figurès et chromolithographies d’après le vivant was an extraordinary book for its time. The book features 41 chromolithographs of living sea creatures and some of the more striking art of octopuses and squids you’ll see.

It was very much a daring enterprise. As Vérany himself recalled later on, he was not sure what he was doing in the beginning, but still jumped in confidently.

“Despite having no practice at lithography and no knowledge of chromolithography, I launched myself, with courage and confidence, into this enterprise… Thanks to trial and error and patience, I have often succeeded in depicting the softness and transparency that characterize these animals.

What is particularly impressive about Vérany’s depictions is the ethereal aspect of the cephalopods. This drew the attention of many leading naturalists of the time, including Ernst Haeckel, who created probably the most famous octopus art of all time.

But it wasn’t just the art itself that drew admiration, but also the technology behind the process.

Octopuses and chromolithographs

Chromolithography is a color printing technique that evolved from the process of lithography. It was developed in the 19th century and was the first method for printing in color that was both relatively affordable and capable of high-volume production. To put it simply, it was the first mass-production color printing available to mankind.

Like lithography, the technique uses the principle that oil and water do not mix. But while lithography works only with one color, chromolithography uses multiple colors.

Lithography largely works like this:

- An image is drawn with a greasy material (like a special crayon or liquid called tusche) onto a flat surface. This was traditionally a smooth limestone block, but in modern lithography, a metal plate is used.

- The surface is then treated with a mixture of acid and gum arabic that etches the areas of the stone not protected by the grease.

- The stone is moistened with water, which is repelled by the greasy areas but is absorbed in the etched areas.

- Oil-based ink is then rolled onto the stone, which sticks to the greasy image and is repelled by the water-soaked areas.

- A piece of paper is pressed onto the stone, transferring the ink and creating the print.

In chromolithography, a separate stone or plate is used for each color that will appear on the print. In the end, this could mean many stones for a complex image. Each stone must be treated and printed onto the paper one at a time, starting from the lightest and moving on to the darkest. It’s key that the paper is aligned perfectly so that the colors overlap perfectly.

The result of chromolithography offered a depth and richness of colors that were previously unavailable. For depicting the vivid world of octopuses, this is just what was needed.

Science and art

Vérany’s passion for the Mediterranean mollusks continued to produce results. He discovered and identified many species for the first time, and in 1846, he founded the Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Nice. This museum is still open to this day.

There’s one episode that the naturalist recalled that is particularly telling for how passionate he was. Vérany would often talk to fishermen and look at their catch, and one day, he found a red umbrella squid (Histioteuthis Bonelliana) in a fisherman’s net. He took the octopus and placed it in a tub, studying it as it moved about.

“It was at this moment that I enjoyed the astonishing spectacle of the brilliant points whose forms so extraordinarily decorate the skin of this cephalopod; sometimes it was the brightness of the sapphire which dazzled me; sometimes it was the opaline of the topazes which made it more remarkable; other times these two rich colors confused their splendid rays. During the night, the opaline points projected a phosphorescent glare, making this mollusk one of the most brilliant productions of Nature,” the naturalist wrote.

Vérany’s efforts left a long-lasting legacy. He influenced Haeckel and first introduced him to cephalopods. He also influenced novelist Victor Hugo and several other artists and scientists at the time.

His work helped other naturalists and artists at the time get a better understanding of the squids. Although he was mostly a self-taught naturalist, his understanding of color and passion for marine wildlife produced a unique mix and legacy that we cherish to this day.