Periodical cicadas spend 99.5% of their life underground. Most of them live in large broods that go underground for cycles of 17 or 13 years — though some have different timings. During these periods, they live as nymphs that feed on fluids from the roots of trees. When the time is right, the individuals in a brood emerge, all at once, and live overground for only a few weeks.

Cicadas likely developed this evolutionary strategy to avoid predators. Using prime numbers for their emergence makes it difficult for predators to adapt. Furthermore, the synchronized, mass emergence of the cicadas, overwhelms predators with sheer numbers and ensures that enough cicadas survive to reproduce and restart the cycle.

A stunning adaptation

When we say “cicada”, we typically refer to the seven species of a genus called Magicicada. These cicada species live only in North America, and especially in eastern North America. They are sometimes called “locusts” — this is a misnomer. Cicadas are entirely different insects from locusts.

Also, not all cicadas are periodical. Some are annual, meaning they appear every summer. A classic example of these annual cicadas can be found in Japan, where the sound of summer is essentially synonymous with cicadas. There are also multiple genera of annual cicadas (including Neotibicen or Neocicada).

But the 13 and 17 year cycles are peculiar and extremely rare in nature.

Nature and prime numbers don’t usually go hand in hand; and both 13 and 17 are prime numbers. This hints that cicadas do this exactly to avoid nature, specifically the cyces of their predators. Since predators like birds and rodents have life cycles that might typically span two to five years, emerging every 17 years minimizes the likelihood that predators could synchronize their own population booms with the cicadas’ appearances.

Cicada broods and predator satiation

In 1907, entomologist Charles Lester Marlatt studied different broods in the US, noting the durations of their cycles. These broods can have many millions of individuals — this is also part of the cicadas’ evolutionary strategy.

Some have over 1.5 million individuals per acre (>370/m), swarming the environment. When they come out of the ground, they are easy prey for basically everything. Reptiles, birds, cats, even squirrels can prey on cicadas. Predators that actively rely on cicadas might have been deterred by the long-term cycle, but occasional predators are still around.

So cicadas do something pretty straightforward: they overwhelm with numbers. This a survival trait called predator satiation and it basically means there’s too many cicadas for the occasional predators to eat.

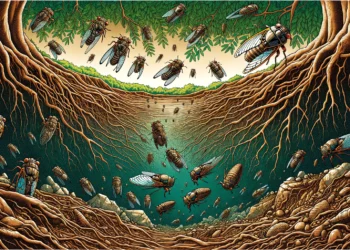

Cicadas emerging from underground

Contrary to popular belief, cicadas aren’t hibernating underground, they’re very much active. In their wingless nymph forms, they’re digging tunnels and moving about, feeding on the xylem from tree roots. They mostly live within 2 ft (61 cm) of the surface, moving deeper and feeding on thicker roots as they mature.

However, cicadas can’t obtain all the nutrients they need from plant juices. They also rely on symbiotic bacteria that provide essential vitamins and nutrients in exchange for some of the cicada’s energy.

The exact mechanisms that cue the cicadas to emerge synchronously after 17 years are not entirely understood, but researchers believe it involves a mix of hormonal changes triggered by tree sap, which they feed on, and environmental cues. Ground temperature is a significant factor. Cicadas typically emerge en masse when the soil eight inches beneath the surface reaches 64 degrees Fahrenheit.

This temperature threshold triggers a biological clock inside the cicadas, starting their transformation from nymph to adult. This synchronized emergence is critical because it enables mass breeding, necessary for the survival of their species.

The cicadas come out between late April and early June. Each brood emerges in a single evening, when the darkness offers some protection from predators. For the rest of their lives, however, the cicadas will be diurnal.

Cicadas, humans, and the environment

Cicadas by their very nature and numbers have an effect on the environment when they emerge. For instance, tree growth is reduced the year before cicadas emerge because the insects eat more and more roots. Also, moles which feed on cicada nymphs, do well before cicadas emerge, but less well in the first years after the cicadas go underground. Of course, there is also the predator feeding frenzy that occurs during their emergence, providing a bounty for surface-dwelling predators.

Once upon a time humans could also be counted among the cicada’s predators. Most cicadas are edible — and Native Americans used to fry and eat them. However, they were more a curiosity than an actual, reliable food. American entomologist Charles Lester Marlatt wrote:

“The use of the newly emerged and succulent cicadas as an article of human diet has merely a theoretical interest, because, if for no other reason, they occur too rarely to have any real value.” So, don’t expect to see them on supermarket shelves any time soon.

During the current emergence, it’s important to remember cicadas aren’t only affecting us — we affect them as well. Climate heating is changing the cycles of cicadas, making them come out earlier, when the environment may not yet be suitable for them. Human intervention also favors the development of a fungus that can affect cicadas.

The remarkable adaptation of cicadas, particularly those with prime-numbered emergence cycles, highlights a sophisticated natural mechanism. This strategy, while seemingly simple, is a powerful testament to the intricacies of evolutionary biology.

This periodic event shouldn’t be frightful or annoying — it’s a testament to natures wonderous adaptations.