Viscosity is a liquid’s property of resisting deformation, such as flow. At home, you probably know this property as the ‘thickness’ of a fluid. The word comes from the Latin word “viscum”, meaning ‘mistletoe’, the berries of which were used in ancient times to create glue.

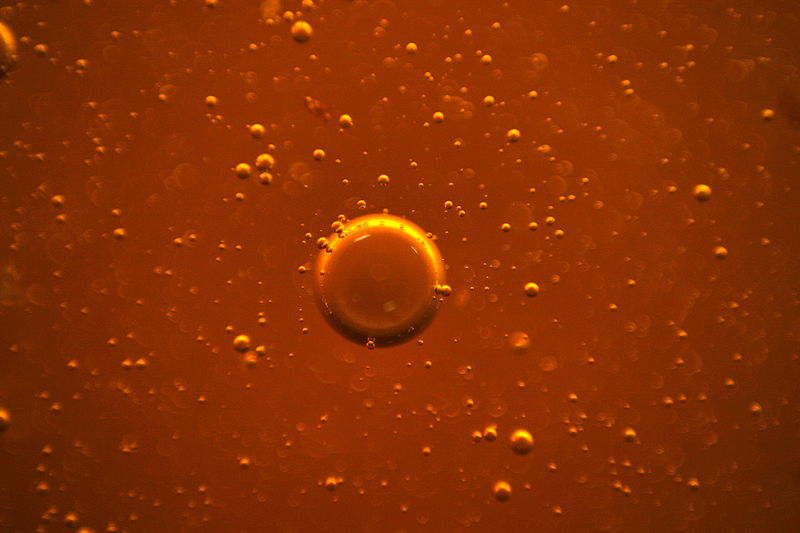

Image via Pixabay.

Viscosity can be a weird concept to wrap your head around, because it makes fluids act not like fluids. Such a large part of our intuitive understanding of fluids relies on them behaving a certain way. Water, the quintessential liquid, flows immediately when poured; it takes the shape of its container, and if there’s no container, it spills everywhere. It gets absorbed by sponges or soil; it bubbles with gusto when boiling.

On the other hand, pitch can easily be confused for a solid. Because it’s so highly viscous, it barely flows, has quite an easy time maintaining its rough shape, and barely percolates through either soil or sponges.

So let’s see what this property which makes fluids un-fluid-like is.

The source of viscosity

In strictly physical terms, viscosity is a fluid’s shear stress over its shear rate, and is expressed in poise (P), a measure of pressure per second. It shows how much force per unit of area you need to apply to make a fluid move (shear stress) and how the internal layers of that fluid will move in respect to one another (shear rate).

In short, it shows how much energy you need to apply to make a fluid flow. The field of science that studies the flow patterns of matter is called rheology from the Greek term “rheo”, meaning ‘flow’.

Viscosity is the product of internal friction between the fluid’s molecules. Both gases and liquids have viscosity, but the molecules in liquids are packed in more tightly — making them interact more and, thus, have higher viscosity than gases.

Image via Pixabay.

Shear rate is important in this equation because it describes how successive ‘layers’ of molecules in fluid interact with one another. A great way to see it in action is to try pouring honey out of a jar. It flows much more slowly than water because it is more viscous than it. But you’ll also notice that the honey in the center will flow out before the honey on the sides of the jar does as well.

This is due to the friction between the layers we mentioned earlier. Honey molecules that are right next to the glass will be attracted to the molecules in glass strongly enough that they’re basically stationary (solids are dense bunches of immobile molecules). They will generate friction with other honey molecules, in turn.

Friction always opposes the direction of motion so, in effect, this stops the fluid from sliding off the glass. Further layers of honey also experience friction, but against layers of fluid that are more mobile than the glass — so there’s less friction. Keep the model going and honey right in the middle of the jar will be most flowy because it’s experiencing little friction (against other relatively mobile molecules of honey).

It doesn’t only slow down pouring fluid — viscosity also prevents objects from passing through. A spoon will go through water with almost no effort, but not so through honey.

Image via Wikimedia user Sichnoy.

A good way to think about viscosity is that all the molecules in a fluid have hands, and they’re using them to hold onto their neighbors. The better these molecules can latch on, the more viscous the substance will be. In physical terms, these hands make up the cohesive force, being generated by chemical and physical interactions between molecules.

Types of viscosity

True solids cannot be vicious. In solids, molecules cannot really move in relation to one another. If one moves, they all move, or break apart. Since viscosity is defined in relation to flow (where particles move independently from one another), it can’t by definition be applied to a true solid. It would be like trying to define what light tastes like. That being said, not all fluids are born equal in regard to viscosity.

The most common class of viscous material you’ll encounter are Newtonian fluids. These always behave like fluids should, having a relatively constant viscosity. Although their resistance to flow does increase as more force is applied, this is proportional to the force being applied. Newtonian fluids, for all intents and purposes, keep acting like fluids no matter how much force you exert on them.

Air is a Newtonian fluid, although viscosity has no bearing on the speed of sound through air.

Image credits Reddit user u/Lord_Rae.

On the other end of the spectrum, we have non-Newtonian fluids. With them, viscosity varies very strongly with the force being applied, but not necessarily in the same way between different materials. Silly putty is a good example; left to itself, it’s somewhat flabby, but when you apply force against the putty, it hardens up. There are three large categories of non-Newtonian fluids: dilatant (apparent viscosity increases with exerted force), pseudoplastic (apparent viscosity decreases with exerted force), and generalized Newtonian fluids (which, ironically enough, are non-Newtonian). Ketchup is also non-Newtonian, but it becomes less viscous when force is applied.

Electrorheological and magnetorheological fluids increase their viscosity in the presence of electrical and magnetic fields respectively and can become near-solid under the right conditions, and quickly reverting back to a liquid if needed.

What has viscosity ever done for you?

Perhaps one of the most important impacts viscosity has on our lives is in our biology. The size, shape, and structure of our hearts, circulatory system and virtually every other tissue, as well as the structures and functionality of our cells, are all shaped to take advantage of or work around viscosity. Our immune system relies in no small part on our lymph channels. Lacking the propelling power of our heart, lymph vessels have to be designed around the viscosity of lymph to keep everything in working order.

Each morning, when you go brush your teeth, it’s viscosity preventing the paste in the tube from splattering everywhere. Without viscosity, your ketchup would drain out of the bottle almost instantly, and the lubricants in your car wouldn’t be able to coat (and thus, lubricate) anything.

Viscosity is what makes liquids want to pool together, and it was a key player in applications such as pill manufacturing. Industries involved in the production of food, chemicals, adhesives, biofuels, paints, medicine, and petroleum processing all keep a close eye on the viscosity of their products.

Finally, viscosity is always affecting us, although we’ve evolved to not feel it. But whenever you make even the slightest of motions, the air’s viscosity works against it — it produces ‘air drag’. Swimming, too, lets you experience a somewhat more concentrated flavor of viscosity.

Personally, I find that processes happening mostly in the background of our awareness, the unsung underdogs of physics (such as viscosity) are the most fascinating ones to study. We may take them for granted, we may not even be aware they exist, but they silently play a part in everything we do. Even a ‘humbler’ one, like viscosity, has directly shaped life on Earth into what it is today.