Nestled within the heart of Venezuela’s Canaima National Park, Angel Falls reigns as the undisputed king of waterfalls. But Angel Falls’ kingdom only stretches above ground.

The world’s largest waterfall is actually underwater, located in the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland. Towering at more than three kilometers high, it is three times taller than Angel Falls. Every second, more than three million cubic meters of cold, dense water emanates from the strait.

The Denmark Strait’s underwater waterfall — known as the Denmark Strait cataract — plays a pivotal role in the intricate dance of the Atlantic’s thermohaline circulation, which influences our planet’s climate on a global scale. The journey begins in the Arctic, where surface water cools and gains density, causing it to sink and flow toward lower latitudes.

Following the contours of the seafloor, this immense current accelerates as it encounters the submarine relief of the Denmark Strait, transforming into a breathtaking waterfall beneath the waves. Eventually, it converges with the great troughs of the northern Atlantic Ocean, leaving an indelible mark on the deep-sea ecosystems thriving in the area.

Unveiling the unknown depths of the world’s tallest waterfall

While the scientific community has dedicated considerable efforts to studying the hydrodynamic properties of this underwater marvel, many aspects of its behavior remain shrouded in mystery.

This is where the FAR-DWO oceanographic campaign, led by Professors David Amblàs and Anna Sanchez-Vidal from the University of Barcelona, comes in.

From July 19 to August 12, 2023, the team boarded the oceanographic ship Sarmiento de Gamboa and embarked on an unprecedented journey.

“To date, we have examined the hydrodynamic characteristics of this colossal underwater cataract. However, in the FAR-DWO expedition, our goal is to delve into unexplored realms,” explained David Amblàs and Anna Sanchez-Vidal from the University of Barcelona’s Department of Earth and Ocean Dynamics.

“We will investigate its capacity to transport sediments, its role in shaping the seabed relief, and the influence of topography on its propagation.”

During the campaign, the team analyzed the hydrographic and sedimentological variability of the waterfall by sampling and observing the water column, as well as studying the sediment and seafloor relief. Two lines equipped with instruments were deployed at great depths, continuously recording hydrological information until their recovery in September 2024. The results are still pending.

The researchers in Barcelona have quite a bit of experience. Their groundbreaking 2008 study revealed the existence of dense water cascades in the Cap de Creus canyon, along the northern coast of Catalonia in the northwestern Mediterranean.

Since then, the GRCGM-UB has spearheaded monitoring initiatives using sediment traps, current meters, and temperature sensors, studying dense water cascades both in the Cap de Creus canyon and polar regions.

“By intensifying and expanding our monitoring efforts, encompassing the Cap de Creus canyon and the Denmark Strait waterfall, we create an ideal frame of reference to investigate current propagation, associated biogeochemical fluxes, and their influence on the seafloor and sedimentary record,” the researchers said.

They plan to combine observational data from both marine areas with a numerical hydrosedimentary model, providing a groundbreaking quantification of the underwater cascades’ transformative power.

The FAR-DWO project will also examine cascade variability in response to current and past climate changes, utilizing historical observations, oceanic and atmospheric models, and sedimentological and geochemical indicators within marine sediment cores.

“Through historical observations, review of oceanic and atmospheric models, and sedimentological and geochemical indicators in marine sediment cores, it will be possible to reconstruct the evolution of these oceanographic processes under different past climate scenarios”, the team explains,” the team wrote.

An illusion beneath the water’s surface

Underwater waterfalls may sound like a contradiction. After all, how can water fall from any height if it’s surrounded by water? But it does make sense because there’s a “waterfall effect” in action, produced by the movement of dense, sediment-laden water descending into deeper areas.

These currents are driven by a variety of factors, including temperature and salinity gradients, tides, and oceanic circulation patterns. However, the human eye wouldn’t be able to detect underwater waterfalls simply because the water looks the same.

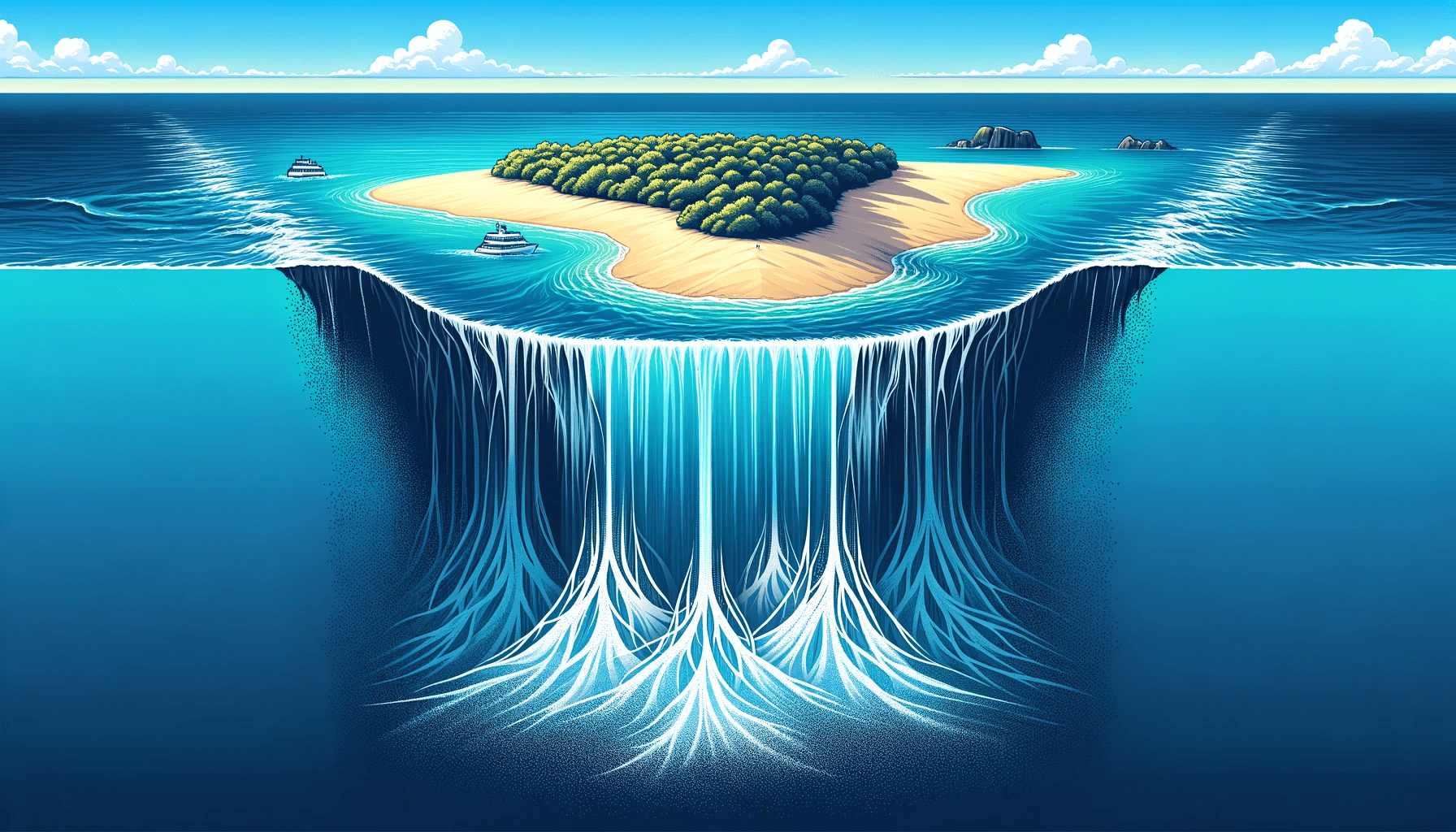

One of the most notable underwater waterfalls is found in Mauritius, one of the most breathtaking islands in the world. Unlike the Denmark Strait, Mauritius’ spectacular underwater waterfall is not subjected to any significant temperature gradient or continuous flows of water from a higher depth.

The secret to Mauritius’ underwater waterfalls is actually sand. Mauritius, a volcanic island, boasts abundant sandy shores. As ocean currents surge, they shuttle this sand back and forth along the shallow shelves that fringe the island.

The shallow shelves, part of a submarine plateau, ultimately yield to deeper, darker waters. It is here, at the southern tip of Mauritius, where the enchantment unfolds.

When ocean currents propel the coastal sand off the island’s edge, it cascades into the abyss below. What appears to be an underwater waterfall is, in fact, the sand sinking through the deep waters, descending to the ocean’s floor. You can call it an optical illusion, but it’s still breathtaking!