For residents of the Eastern and Midwestern United States, 2024 is shaping up to be a symphony of buzzing wings and crunchy exoskeletons. This year is extra special as Brood XIII, a 17-year cicada brood, and Brood XIX, a 13-year brood, are emerging in a synchronized spectacle not witnessed since 1803. To celebrate the momentous occasion, here are some interesting facts about one of nature’s most amazing critters.

They emerge only every 13 or 17 years

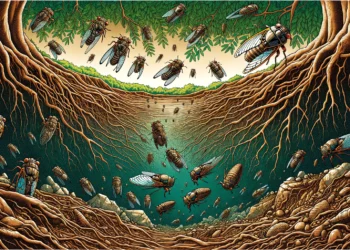

For 13 or 17 years, depending on the brood, cicada nymphs patiently feed on tree roots underground, existing in a state of developmental arrest. An internal biological clock triggers their synchronized emergence. This molecular clock keeps track of the passing years, most likely tied to tree biochemistry like the composition of the xylem fluid on which they feed. In the final year, when the soil temperature reaches a specific point, typically around 64 degrees Fahrenheit (17.8 degrees Celsius), a complex hormonal cascade is triggered within the nymphs, prompting them to dig their way to the surface en masse.

They don’t hibernate underground. In fact, they’re still active for all these years

It’s a common misconception that periodical cicadas spend all these years underground in hibernation. During their lengthy underground stay, cicada nymphs are constantly digging and burrowing. They create elaborate tunnel networks that can reach depths of several feet. These tunnels not only help them access food sources but also contribute to soil aeration, benefiting the very trees they feed on. However, in their adult form as flying insects, the lifespan of periodical cicadas is only a few weeks. By mid-July, all the cicadas will die.

The prime number cycles are for protection

Periodical cicadas emerge in 13- and 17-year life cycles for protection against predators. By emerging on prime number cycles, cicadas aim to avoid encountering predators with synchronized breeding cycles. However, this strategy can backfire if a brood experiences a significant environmental disruption, like deforestation, that throws off their timing and makes them more vulnerable. Their other strength lies in their sheer numbers. During the emergence, trillions of cicadas swarms flood the landscape, far too many to finish off even for the hungriest birds.

They’re nature’s recyclers

While they may be a nuisance to some, cicadas play a vital role in the ecosystem. After their short adult lifespan, their decomposing bodies become a rich source of nitrogen, nourishing the very trees they fed on as nymphs

The 3,339 species of cicadas live on every continent except Antarctica — but there are only seven species of periodical cicadas

Cicadas are divided into two subfamilies: the Tettigarctidae, with only two species in Australia, and the Cicadidae, with more than 3,000 species described across the world, with many remaining undescribed. However, only the exclusively North American genus Magicicada — what we call periodical cicadas — emerge every 13 or 17 years. “Normal” cicadas emerge every year, which is why they’re simply called “annual cicadas”.

Only males produce the loud buzzing noise typical of cicadas

Male cicadas exclusively produce their signature sound, often described as a high-pitched whine or a buzz, by rapidly vibrating a specialized membrane on their abdomen called a tymbal. This rapid vibration pushes air through tiny openings, creating the sound. The sound is amplified by the insect’s hollow abdomen which acts as a resonance chamber. The louder the cicada calls, the more attractive they are to females. Interestingly, some cicada species have different songs.

These songs can reach up to 90 decibels, roughly the same volume as a lawnmower, and can be quite deafening in large numbers and up close. The cicadas themselves don’t seem to care. They have their own ‘earmuffs’ to shield them from their powerful emissions. The insects have a set of tympana — mirror-like membranes that function as ears — that can temporarily disable their hearing to prevent damage while singing.

They don’t pose any threat to humans

Cicadas don’t sting or bite and pose no threat to humans. They do make a lot of racket and unpleasant smells, but they’re not dangerous at all. However, female cicadas can damage young trees when laying their eggs. Their ovipositor, a sharp egg-laying apparatus, can cause small wounds in branches as they deposit their eggs. These wounds can weaken branches and make them susceptible to breakage. Fortunately, this can be easily prevented by covering vulnerable branches with cheesecloth during the emergence period.

Some predators have a sweet tooth for ciadas

While cicadas are a valuable source of protein for many predators, some insects have developed a more specialized taste. Cicada killer wasps (Sphecius speciosus) are solitary, two-inch-long wasps that paralyze cicadas with their venomous sting and use them as provisions for their offspring.

The insects form ‘cicada rain’ out of their pee

The mass emergence of cicadas can sometimes lead to a phenomenon called “cicada rain.” This doesn’t involve actual raindrops, but rather the expulsion of excess fluids from the cicadas’ bodies — yes, it’s basically cicada pee. As they prepare to molt, they expel this liquid that looks a lot like watery tree sap. While not exactly pleasant, it’s harmless and eventually dries up.

A horrible fungus can turn them into sex-crazed zombies

Cicadas can fall victim to a particularly gruesome parasitic fungus called Cordyceps. Yes, it’s the same microbial agent responsible for the human zombies in the The last of Us franchise. This fungus infects the cicada and takes control of its body, eventually pushing a fruiting structure out of the cicada’s head. As if that wasn’t gruesome enough, another parasitic fungus called Massospora cicadina causes the cicada’s genitals to decompose and makes the insects hyper-sexual, further spreading this cicada STD.

Some people actually eat them

While cicadas are enjoyed as a delicacy in some parts of the world, their taste is a matter of debate. Some describe them as nutty and flavorful, while others find them bland or even unpleasant.

Cicadas, particularly the young tenerals, are incredibly versatile as a culinary ingredient, offering a unique, shrimp-like flavor when prepared correctly. According to the University of Maryland’s Cicada-licious cookbook, the best time to harvest these white-green bugs is in the early morning hours from tree trunks, storing them in a paper bag. To maintain their texture, it’s advisable to cook them immediately or refrigerate them, though freezing is the most humane method of euthanasia.

Before cooking — through methods like boiling, blanching, frying, or roasting — remove the non-flavorful hard parts such as wings and legs. Cicadas can be incorporated into a variety of dishes, from dumplings and banana bread to more creative preparations like tempura-fried cicadas and cicada-infused sushi and pasta, where they provide an earthy taste reminiscent of shrimp.