Protected areas are advocated for by scientists and conservationists alike because of their clear environmental benefits. Due to the constant expansion of our species, environments and ecosystems are under more and more pressure, and having safe havens like these protected areas is essential for the wellbeing of our planet.

Primarily, protected areas protect biodiversity and ecosystems while also often functioning as natural climate solutions. Protected areas also come with a host of benefits for goals beyond environmentalism. These include social and financial benefits for residents within protected areas and safeguarding against the emergence of new zoonotic diseases. Simply put, protected areas are not just good for the planet — they’re good for us as well.

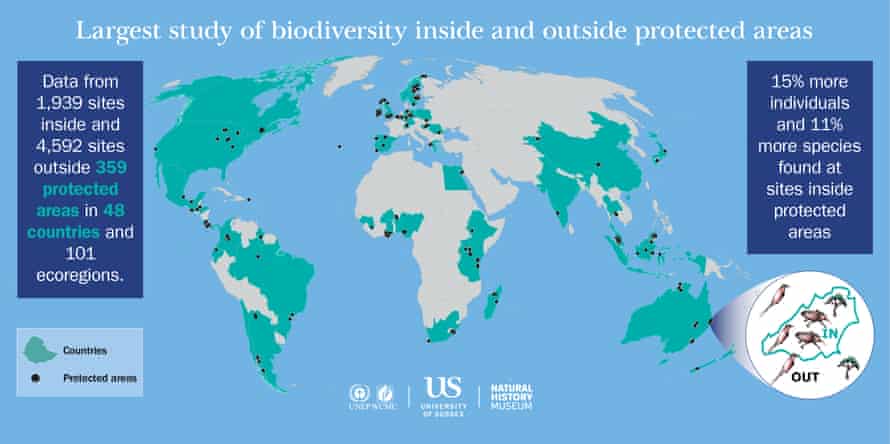

Currently, around 15% of Earth’s land surface (and around 7% of Earth’s ocean surface) is protected. There is therefore a long way to go before we reach the 50% protection goal.

However, in urging our governments to reach this 50% target, some scientists have warned us there is a risk that we can get so caught up in the quantity of protected land and seas that we don’t also consider how effective those protected areas are in the first place. But before we talk about the quality of protected areas, let’s talk a bit about quantity.

Where does this 50% figure come from anyway?

Prominent voices that are calling for half the Earth to be protected include the aptly named Half-Earth Project based on the book written by E. O. Wilson, as well as Nature Needs Half, an international organization that advocates for half of the planet to be protected by 2030. Their choice of 50% of the Earth, however, is not an arbitrary one, but one that is supported by science.

The Global Safety Net is a tool developed by a team of scientists that combines a number of different data layers and spatial information to estimate how much of Earth’s terrestrial environment needs to be protected to attain three specific goals. Those goals were 1) biodiversity conservation, 2) enhancing carbon storage, and 3) connecting natural habitats through wildlife and climate corridors.

The researchers found that using this framework, a total of 50.4% of terrestrial land should be conserved to “reverse further biodiversity loss, prevent CO2 emissions from land conversion, and enhance natural carbon removal”. Interestingly, these results concur with prior calls to protect half the planet.

This data also found that, globally, there is significant overlap between the land that needs to be protected for conservation and Indigenous lands. The authors of the paper write that by enforcing and protecting Indigenous land rights, we can combine biodiversity and climate goals with social justice and human rights. They emphasize that “with regard to indigenous peoples, the Global Safety Net reaffirms their role as essential guardians of nature”.

Why it can be detrimental to only look at the numbers

Scientists are absolutely right in saying we should aim to protect half the planet. But there’s more to it than that. An equally important consideration is how effective those protected areas are at achieving their stated goals.

Worryingly, some scientists estimate the true quantity of protected land is much lower than the official 15% when effectiveness is considered. One paper found that “after adjusting for effectiveness, only 6.5%—rather than 15.7%—of the world’s forests are protected”. Importantly, the authors caution their readers against assuming that protected areas will completely eliminate deforestation within their boundaries. On average, they found that protected areas only reduced deforestation by 41%.

Another team of scientists analyzed over 50,000 protected areas in forests around the world and their impact from 2000-2015. A major finding from their paper was that a third of protected areas did not contribute to preventing forest loss. In addition, the areas that were effective only prevented around 30% of forest loss. The authors call for improving the effectiveness of existing protected areas in addition to expanding protected area networks.

Finally, a team of researchers recently authored a paper that analyzed protected areas established between 2000 and 2012 and found that significantly more amounts of deforestation could be avoided if existing protected areas were made more effective — this was despite the authors stating that protected areas already reduce deforestation by 72%. This is a notably higher effectiveness than is stated by those other papers – perhaps because the team analyzed only protected areas that were established relatively recently. Multiple papers have found that newer protected areas tend to be on average more effective than older ones.

So how can we make protected areas more effective then?

One of the most important considerations is that protected areas tend to prevent more deforestation in areas where deforestation is higher. However, it is still important to protect lands currently at low risk of degradation. In that way, future forest loss can be prevented before it becomes a significant problem.

Indirectly, other attributes of a country can predict how effective or ineffective the protected areas within that nation will be. Countries that have higher human development, higher GDP per capita, better governance, and lower agricultural activity tend to host more effective protected areas than countries with lower human development and GDP per capita, lower government effectiveness, and higher levels of agriculture.

Finally, as mentioned before, there is a huge amount of overlap between potential land for protection and Indigenous land. Engaging with, and granting property rights and legal recognition to, Indigenous people is a cost-effective way to protect forests while also addressing a human rights issue at the same time.

What all of this data shows us is that the conversation surrounding environmental protection needs to be considered in a broader context, and take into consideration economic, political, and social justice concerns. And it is an issue that is far too complex for its success to be measured by a single number.