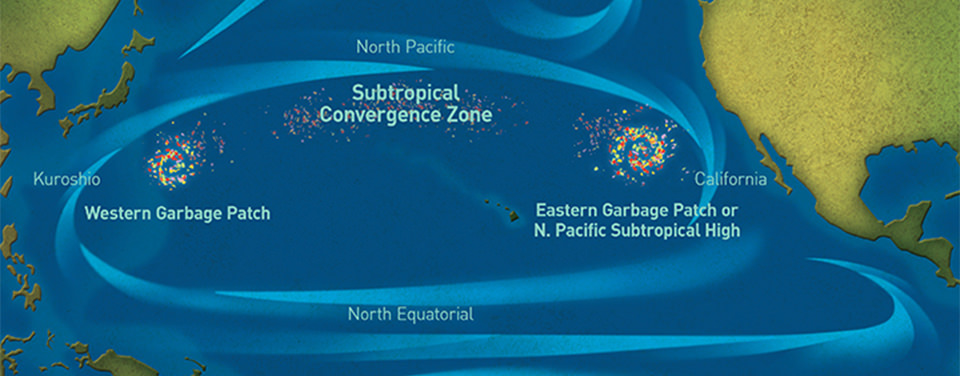

Every year, approximately eight million tons of plastic find their way to our oceans. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a collection of marine debris in the North Pacific, is the poster child of this haphazard waste disposal byproduct. You may have heard it called the Pacific trash vortex. It is comprised of Western Garbage Patch, located near Japan, and the Eastern Garbage Patch, located between the U.S. states of Hawaii and California. The litter spans from the American west coast all the way to Japan. But one may wonder…how did it get there exactly?

Researchers in the U.S. and Germany decided to find out. In a new study published in the journal Chaos, they created a Markov chain model of the oceans’ surface dynamics from historical trajectories of surface buoys. Their model describes the probability of plastic debris being transported from one region of ocean surface to another.

“Surface debris is released from the coast and distributed according to their location’s share of the global land-based plastic waste entering the ocean,” said Philippe Miron, an assistant scientist at the University of Miami and a co-author of the study. “To observe the long-term distribution of floating debris, beached debris is reinjected into the system following the same distribution. We call this model ‘pollution aware,’ because it models the injection, dispersion, and recirculation of debris within the system.”

Their work focused on areas from the coasts to the subtropical gyres — or rotating ocean currents — to try and identify pathways or transition paths that connected the trash sources directly to the areas of the Pacific harboring the waste. It is actually possible to sail through these garbage patches seeing very little, or even no, evidence of this trash.

Wind, tides, and differences in temperature and salinity drive ocean currents. The ocean will churn up the different types of currents like eddies, whirlpools or deep ocean currents. Larger, more sustained currents, such as the Gulf Stream located in the Atlantic, go by proper names. Taken together, these larger and more permanent currents make up the systems of currents known as gyres.

There are five major gyres: the North and South Pacific Subtropical Gyres, the North and South Atlantic Subtropical Gyres, and the Indian Ocean Subtropical Gyre.

In some instances, the term “gyre” is used to refer to the collections of plastic waste and other debris which can be found in higher concentrations of certain parts of the ocean. While this use of the term is increasingly common, the name traditionally refers simply to large, rotating ocean currents.

The researchers inferred these debris pathways and searched for garbage patch stability by quantifying the connection between them and their ability to retain the litter. What they found was that generally the gyres they studied were weekly connected or even disconnected altogether.

“We identified a high-probability transition channel connecting the Great Pacific Garbage Patch with the coasts of eastern Asia, which suggests an important source of plastic pollution there,” said Miron. “And the weakness of the Indian Ocean gyre as a plastic debris trap is consistent with transition paths not converging within the gyre…Indeed, in the event of anomalously intense winds, a subtropical gyre is more likely to export garbage toward the coastlines than into another gyre.”

One of the biggest discoveries the group made is while the North Pacific subtropical gyre will attract the most debris, the South Pacific gyre actually stands out as the most enduring, because debris has fewer pathways out and into other gyres.

“Our results, including prospects for garbage patches yet to be directly or robustly observed, namely in the Gulf of Guinea and in the Bay of Bengal, have implications for ocean cleanup activities,” said Miron. “The reactive pollution routes we found provide targets — aside from the great garbage patches themselves — for those cleanup efforts.”