The Environmental Protection Agency made news recently for excluding reporters from a “summit” meeting on chemical contamination in drinking water. Episodes like this are symptoms of a larger problem: an ongoing, broad-scale takeover of the agency by industries it regulates.

We are social scientists with interests in environmental health, environmental justice and inequality and democracy. We recently published a study, conducted under the auspices of the Environmental Data and Governance Initiative and based on interviews with 45 current and retired EPA employees, which concludes that EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt and the Trump administration have steered the agency to the verge of what scholars call “regulatory capture.”

By this, we mean that they are aggressively reorganizing the EPA to promote interests of regulated industries, at the expense of its official mission to “protect human health and the environment.”

How close is too close?

The notion of “regulatory capture” has a long record in U.S. social science research. It helps explain the 2008 financial crisis and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. In both cases, lax federal oversight and the government’s over-reliance on key industries were widely viewed as contributing to the disasters.

How can you tell whether an agency has been captured? According to Harvard’s David Moss and Daniel Carpenter, it occurs when an agency’s actions are “directed away from the public interest and toward the interest of the regulated industry” by “intent and action of industries and their allies.” In other words, the farmer doesn’t just tolerate foxes lurking around the hen house – he recruits them to guard it.

Serving industry

From the start of his tenure at EPA, Pruitt has championed interests of regulated industries such as petrochemicals and coal mining, while rarely discussing the value of environmental and health protections. “Regulators exist,” he asserts, “to give certainty to those that they regulate,” and should be committed to “enhanc(ing) economic growth.”

In our view, Pruitt’s efforts to undo, delay or otherwise block at least 30 existing rules reorient EPA rule-making “away from the public interest and toward the interest of the regulated industry.” Our interviewees overwhelmingly agreed that these rollbacks undermine their own “pretty strong sense of mission … protecting the health of the environment,” as one current EPA staffer told us.

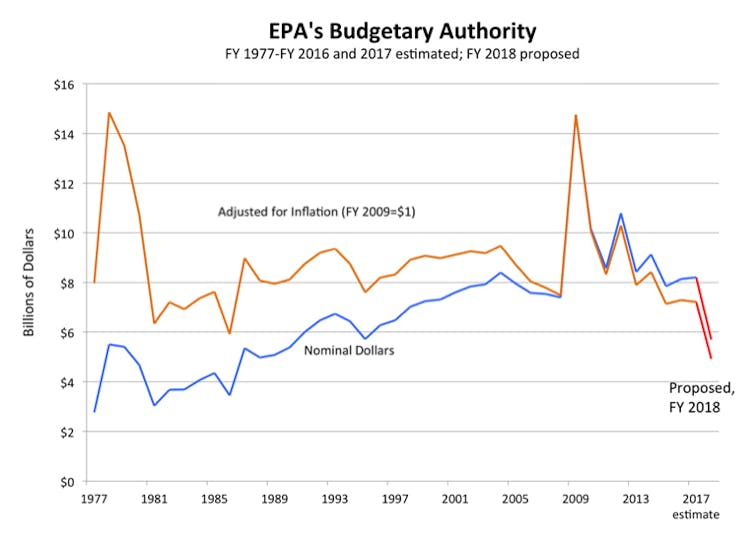

EDGI, CC BY-ND

Many of these targeted rules have well-documented public benefits, which Pruitt’s proposals – assuming they withstand legal challenges – would erode. For example, rejecting a proposed ban on the insecticide chlorpyrifos would leave farm workers and children at risk of developmental delays and autism spectrum disorders. Revoking the Clean Power Plan for coal-fired power plants, and weakening proposed fuel efficiency standards, would sacrifice health benefits associated with cutting greenhouse gas emissions.

A key question is whether regulated industries had an active hand in these initiatives. Here, again, the answer is yes.

Nuzzling up to industry

Pruitt’s EPA is staffed with senior officials who have close industry ties. For example, Deputy Administrator Andrew Wheeler is a former coal industry lobbyist. Nancy Beck, deputy assistant administrator of EPA’s Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, was formerly an executive at the American Chemistry Council. And Senior Deputy General Counsel Erik Baptist was previously senior counsel at the American Petroleum Institute.

Documents obtained through the Freedom of Information Act show Pruitt has met with representatives of regulated industries 25 times more often than with environmental advocates. His staff carefully shields him from encounters with groups that they consider “unfriendly.”

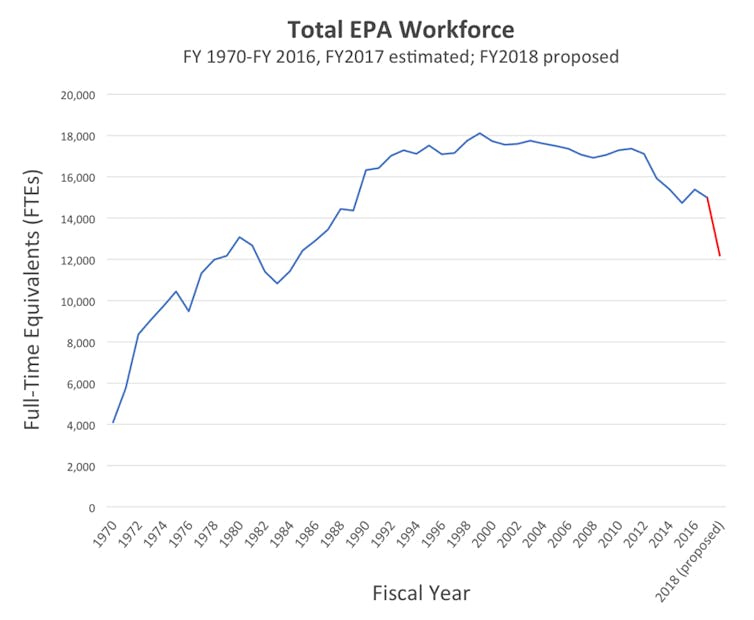

EDGI, CC BY-ND

The former head of EPA’s Office of Policy, Samantha Dravis, who left the agency in April 2018, had 90 scheduled meetings with energy, manufacturing and other industrial interests between March 2017 and January 2018. During the same period she met with one public interest organization.

Circumstantial evidence suggests that corporate lobbying is directly influencing major policy decisions. For example, just before rejecting the chlorpyrifos ban, Pruitt met with the CEO of Dow Chemical, which manufactures the pesticide.

Overturning Obama’s Clean Power Plan and withdrawing from the Paris climate accord were recommended by coal magnate Robert Murray in his “Action Plan for the Administration.” Emails released under the Freedom of Information Act show detailed correspondence between Pruitt and industry lobbyists about EPA talking points. They also document Pruitt’s many visits with corporate officials as he formulated his attack on the Clean Power Plan.

Muting other voices

Pruitt and his staff also have sought to sideline potentially countervailing interests and influences, starting with EPA career staff. In one of our interviews, an EPA employee described a meeting between Pruitt, the home-building industry and agency career staff. Pruitt showed up late, led the industry representatives into another room for a group photo, then trooped back into the meeting room to scold his own EPA employees for not listening to them.

Threatened by proposed budget cuts, buyouts and retribution against disloyal staff and leakers, career EPA employees have been made “afraid … so nobody pushes back, nobody says anything,” according to one of our sources.

As a result, enforcement has fallen dramatically. During Trump’s first 6 months in office, the EPA collected 60 percent less money in civil penalties from polluters than it had under Presidents Obama or George W. Bush in the same period. The agency has also opened fewer civil and criminal cases.

Early in his tenure Pruitt replaced many members of EPA’s Science Advisory Board and Board of Scientific Counselors in a move intended to give representatives from industry and state governments more influence. He also established a new policy that prevents EPA-funded scientists from serving on these boards, but allows industry-funded scientists to serve.

And on April 24, 2018, Pruitt issued a new rule that limits what kind of scientific research the agency can rely on in writing environmental regulation. This step was advocated by the National Association of Manufacturers and the American Petroleum Institute.

What can be done?

This is not the first time that a strongly anti-regulatory administration has tried to redirect EPA. In our interviews, longtime EPA staffers recalled similar pressure under President Reagan, led by his first administrator, Anne Gorsuch.

Gorsuch also slashed budgets, cut back on enforcement and “treated a lot of people in the agency as the enemy,” in the words of her successor, William Ruckelshaus. She was forced to resign in 1983 amid congressional investigations into EPA misbehavior, including corruptive favoritism and its cover-up at the Superfund program.

EPA veterans of those years emphasized the importance of Democratic majorities in Congress, which initiated the investigations, and sustained media coverage of EPA’s unfolding scandals. They remembered this phase as an oppressive time, but noted that pro-industry actions by political appointees failed to suffuse the entire bureaucracy. Instead, career staffers resisted by developing subtle, “underground” ways of supporting each other and sharing information internally and with Congress and the media.

Similarly, the media are spotlighting Pruitt’s policy actions and ethical scandals today. EPA staffers who have left the agency are speaking out against Pruitt’s policies. State attorneys general and the court system have also thwarted some of Pruitt’s efforts. And EPA’s Science Advisory Board – including members appointed by Pruitt – recently voted almost unanimously to do a full review of the scientific justification for many of Pruitt’s most controversial proposals.

![]() Still, with the Trump administration tilted hard against regulation and Republicans controlling Congress, the greatest challenge to regulatory capture at the EPA will be the 2018 and 2020 elections.

Still, with the Trump administration tilted hard against regulation and Republicans controlling Congress, the greatest challenge to regulatory capture at the EPA will be the 2018 and 2020 elections.

Chris Sellers, Professor of History and Director of the Center for the Study of Inequalities, Social Justice, and Policy, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York); Lindsey Dillon, Assistant Professor of Sociology, University of California, Santa Cruz, and Phil Brown, University Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Health Sciences, Northeastern University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.